Emperor Rudolf II never did anything by half measures. When he wanted to maintain artificial fish ponds in Prague’s Stomovka park, he had a kilometer-long tunnel built from the Vltava river, under Letná and into the landscaped wooded area. At the time it was private imperial property used as a game preserve.

This was no small feat. Much of what is known as Rudolfova štola, or Rudolfine Tunnel, had to be built through solid rock centuries before the invention of dynamite. Construction took place 1584–93, stopping sporadically when money ran out.

Traces of the tunnel, which still functions, can still be seen at either end as well as along the way. The tunnel is still in good condition, but it is not currently open to the public.

Most people barely notice a small shack not far from the bridge Štefánikův most. That was a technical house called the “havirna,”whichcontrolled the iron sluice gates below the waterline. The shack is neglected and covered in graffiti. The area around it is used for parking, and some boats are docked nearby.

Almost directly above is the popular Letná beer garden, with the newly restored remnants of a cable car platform from 1891. The cable car ran up the hill until 1916. Between the beer garden and the tennis courts, there is a concrete cap for a shaft leading down to the tunnel.

Outside Letná park is the next clue to the tunnel. Just beyond the National Museum of Agriculture (Národní zemědělské muzeum) there is an elementary school called Gymnázium Nad Štolou and the street called Nad Štolou, which means “above the tunnel.” The street actually runs some 45 meters directly above the oval-shaped sewer.

Nad Štolou street joins with Čechova Street, where you can find a turret covering a ventilation shaft. The curious graffiti-covered concrete and rusted iron structure dates to 1906. This street takes you to Stromovka, where you can enter next to a playground.

Keeping as straight as possible and heading down the hill, you get to another squarish shack. Hidden behind that is a stone portal with an arched top. The keystone of the arch has the letter “R” and an imperial crown — the mark of Rudolf II.

This shack currently is being renovated as part of a larger Šlechtovka restoration project. The portal behind it is closed off behind fences until April 2020, but it can be still be seen from just beyond an orange plastic barrier. Graffiti has been removed and hopefully efforts will be made to protect the portal and shack from further vandalism.

Just beyond this are the lakes that the tunnel was meant to fill. These have also been rebuilt, with new paths and benches.

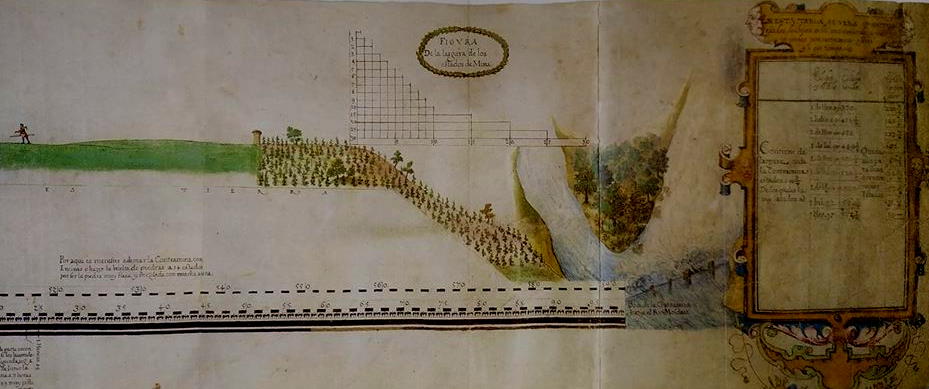

The hand-colored original plans for the tunnel still exist, on a long narrow scroll in the possession of the National Technical Museum, which is located almost exactly above the tunnel. The scroll is 2.5 meters long, and was made by Lazarus Ercker von Schreckenfels, an important 16th century mining engineer. The text is in Spanish, as that was a language both Rudolf II and von Schreckenfels had in common.

The scroll vanished during the looting of Prague at the end of the Thirty Years’ War, and turned up at an auction in Paris in the early 1900s. It was purchased by a private bidder later handed over to what is now the National Technical Museum in 1911.

The tunnel has an oval or egg shape, and runs 1,098 meters long, ranging from 0,8 meters to 1.5 meters wide and 2 to 4 meters in height. The total construction cost was 66,299 groschen.

Many of the miners who built the tunnel had previously worked on the silver mines in Kutná Hora. The first step was to build five vertical shafts, which could be used to haul out the stone and soil to make the horizontal tunnel. The Čechova Street vent is one of these.

Blasting through the rock was difficult task. It involved heating the rock with hot iron rods, and then throwing cold water on the rock to make it shatter.

Miners dug from both ends and met in the middle. The meeting point is a bit wider than planned as the tunnels were off a bit and didn’t join up neatly. The miners had to make some slight deviations along the way to avoid the most difficult terrain.

The tunnel is still maintained by the city, and cleaned out from accumulated muck once a year. The entry by Stromovka was restored and opened to the public in 1997. The restoration was funded by United Distillers as part of a project called Water of Life. It was open sporadically after that until the floods in 2002 forced its closure.

Reading time: 4 minutes

Reading time: 4 minutes