If everything went according to Emperor Charles IV’s plan, Karlovo náměstí would be the city’s main gathering point, and Wenceslas Square would be a quiet marketplace for horses.

Karlovo náměstí was the largest town square in medieval Europe, and still is one of the world’s largest. But despite efforts both in the past and now, Karlovo náměstí just simply never caught on and still is underused. The buildings around the square are filled with both history and legends, and square itself has numerous statues and plaques to remember important people.

PARTNER ARTICLE

New Town (Nové Město) was an early attempt at a planned city. Charles IV planned the development in 1348 loosely based on maps of Jerusalem, and New Jerusalem was one its alternate names. Karlovo náměstí was supposed to correspond to Jerusalem’s Temple Mount.

His idea was that since the actual Jerusalem in the Middle East was lost in the Crusades, a new one was needed. In the long term, it would be where God would return to earth for Judgment Day, and as a planned holy city, God would eternally show his favor to it and its inhabitants.

The square was first known as the Cattle Market (Dobytčí trh), and only in 1848 did it get its current name of Karlovo náměstí (Charles Square). It became a public park about a decade after that.

While the massive St. Ignatius Church (Kostel svatého Ignáce) has been on the east side of square since 1677, there was originally another church in the square. The first Corpus Christi Chapel (Kaple Božího těla), made of wood, was in the center of the square from 1354 until it was replaced by a stone church that stood for 1393 until it was deconsecrated in 1784 and demolished in 1789.

Once a year, on the first Friday after Easter, the chapel would display Christian relics including an alleged nail and a splinter of wood from the True Cross, part of the Crown of Thorns, and Longin’s spear from the Crucifixion, among other religious items collected by Charles IV. Pilgrims would come from far and wide to visit the square and see the relics.

People who died in Prague during the pilgrimage could be buried in the small cemetery next to the chapel. Notable scholars were also buried there. All urban cemeteries were abolished in the late 1700s by Emperor Joseph II in an effort to stop the spread of disease, and the bodies were moved out.

The foundation of the chapel and remnants of several graves were found in 2011 at Ječná and Resslova streets during construction work. The rest of the building’s structural stonework seems to have been taken away to be reused over 200 years ago.

The square’s northeast corner is marked by the New Town Hall (Novoměstská radnice), which among other things, was the site of the First Defenestration of Prague on July 30, 1419. The unceremonious chucking of several Catholic officials out of a window by a Hussite mob soon led to the Hussite Wars.

Next to the main entrance to the hall’s tower is a metal rod embedded in the stone. This was New Town’s official measuring rod for the Prague cubit, or loket, which measures 59.3 centimeters. It was used to settle disputes over lengths of cloth or other measurable items. Another measuring rod can be found near Prague Castle on door of the historical Hradčany Town Hall.

There is a lot more to say about the New Town Hall, but the one building would fill a whole article by itself.

On the exact opposite side of the square on is the Faust House (Faustův dům), where alchemist Edward Kelley is thought to have lived starting in 1587, during the reign of Emperor Rudolf II. The site of the building was once a pagan grove for the winter goddess Morana, whose name can still be found on the tram stop Moráň and street Na Moráni, which meets up with Karlovo náměstí.

The building during the era of Romantic literature in late 1700s became associated with the legend of Faust, probably due to Kelley as well as other alchemists and astrologers having lived there. The site’s pagan roots, plus a series of fires and other calamities that befell the structure also contributed to its mystique. Faust is alleged to have made a deal with the devil for worldly success.

The baroque pink and gray palace is now used by the First Medical Faculty of Charles University and the University Hospital. The original building was built before 1378, and it was remodeled and expanded several times. The current look dates to 1820. It was slightly damaged during an Allied bombing raid in World War II.

Due to cross streets, the square itself is divided into three sections. Since the late 1800s to early 1900s was the golden age of statue building in parks, each section has at least one notable piece. The original design of the park was by garden architect František Josef Thomayer, who also designed Letná park and other public spaces.

The smallest section, near the New Town Hall, has a fountain with a plague column, in memory of the Great Plague of 1679. Also in this strip is a statue and fountain in memory of poet Vítězslav Hálek, with a metal bust, two stone sphinxes and a water-spouting lion’s head. It dates to 1882. Hálek’s most significant work was Fairytales from Our Village (Pohádky z naší vesnice). Along with Jan Neruda, he is considered a founder of Czech poetry.

The next section, between Žitná and Ječná, has a statue of Eliška Krásnohorská and a monumental tree. Krásnohorská was a feminist writer associated with children’s literature, translations, and the texts for four operas by Bedřich Smetana and one opera by Zdeněk Fibich. She also founded the first all-female high school in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It held lessons in the Czech language.

The sleek and unadorned white marble statue, unveiled in 1931, earned sculptor Karla Vobišová-Žáková an award from the Academy of Sciences and Arts.

The tree, now surrounded by a fence, is a sycamore estimated to be 170 years old. Efforts to save it began in 1985 with metal bands and supports. It was declared a national monument in 1998.

The third section of the park, between Ječná and U Nemocnice, is a bit more interesting, with three statue groups.

The metal bust of 19th century author writer Karolina Světlá greets people entering the park from the Karlovo náměstí metro stop. She is known for literary realism and rural themes, as well as her relationship with Jan Neruda.

Her stern and unsmiling face, looking like an evil governess in a Gothic horror film, is by Czech sculptor Gustav Zoula and dates to 1910.

In the center of the park is a sculpture of a seated Jan Evangelista Purkyně. The Czech biologist coined the word “protoplasm” for the substance inside cells. He also wrote and translated poetry,

In the statue by Oskar Kozák and Vladímir Štrunc from 1961, Purkyně bears a slight resemblance to a beardless Abraham Lincoln, and is vaguely similar to the seated statue at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC.

Lost a bit at the far edge of the square is a statue of botanist and traveler Benedikt Roezl, who traveled throughout Latin America finding and naming orchids. He also founded Flora, the first botany magazine in Czech.

The sandstone statue with bronze details, erected in 1898, is by Gustav Zoula and Čeněk Vosmík. Unmentioned in the inscription is an almost nude Native American youth carrying a metal hunting knife. It was previously a bronze machete, but recently it was changed to something a bit smaller. The whole statue is a rather elaborate affair with bronze chains, steps and built-in benches.

The illustrated magazine Zlatá Praha in November 1897 published an article claiming that the statue was made by mistake due to some miscommunication, and that it had been intended to be either zoologist Jan Svatopluk Presl or inventor Josef Ressel (who has a plaque in the on the square as well as Resslova Street, which ends at the square).

The article seems to have been meant in jest, but the claim is often now repeated as fact.

That’s not all of the statues. On the east side of the square in the former Jesuit school buildings, now part of the University Hospital, a memorial for paramedics from World War I is in the parking lot. The group has a solider, a woman and an obelisk, plus plaques with names. It was restored in 2018.

Another hidden artwork is under the square, in the metro station. A large mosaic depicting Emperor Charles IV and life in the 14th century was installed during the communist era in 1985 as part of the station’s art. It was designed by Radomír Kolář and František Tesař.

There’s still more to notice. Plaques on buildings circle the entire square, pointing out significant people who lived there, and marking some significant events.

One the side of Municipal Court building, adjacent to the New Town Hall and facing the park, is a plaque for Christian Doppler, who taught at what is now the Czech Technical University in Prague (ČVÚT).

He lived in a building on the square in 1842 while he was researching the Doppler effect — shifts in light or sound waves due to motion. The whir of a passing siren is an example.

The marble plaque with gold letters, erected in 1903, has a mistake in the date of his death. It was 1853, not 1854. Another plaque for him is at U Obecního dvora, where he also briefly lived.

A red granite plaque at Ječná 550/1 marks where writer Karolina Světlá died, another plaque on the same building says it is the House at the Stone Table (dům U Kamenného stolu). That plaque is by sculptor Jaroslav Horejc.

Poet Karel Hynek Macha wrote his famous poem Májat Karlovo namesti 551/37. Baroque sculptor Matyáš Bernard Braun died at Karlovo náměstí 671/24, known as Braunův dům, or the Braun House.

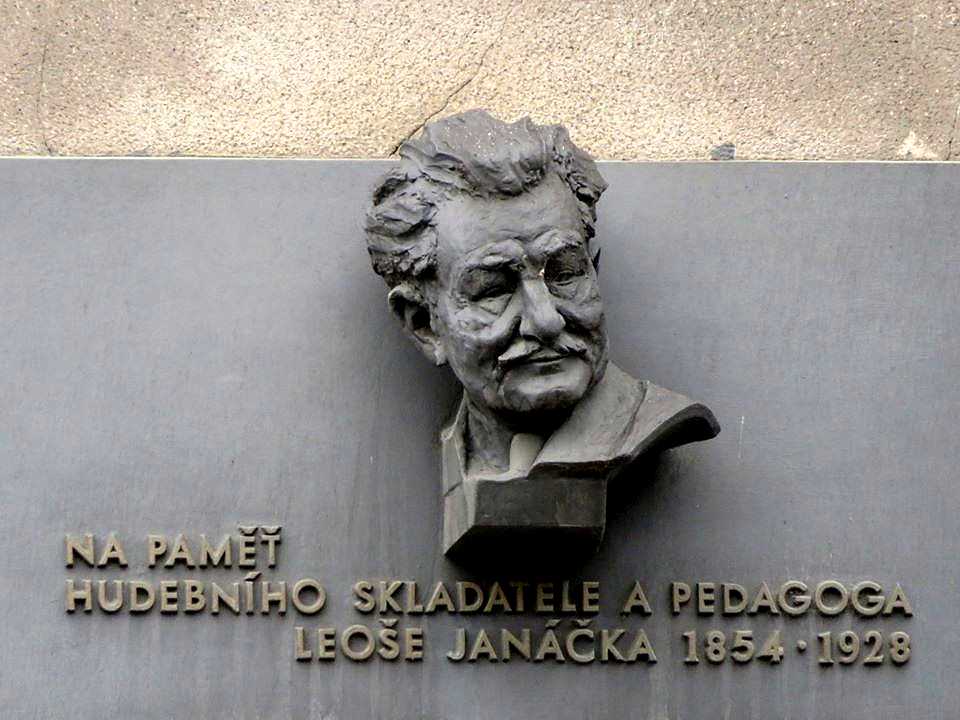

The composer Leoš Janáček has a plaque with a bust at Karlovo namesti 319/3. Violinist and conductor Josef Suk Jr. has a marker with a relief portrait at Karlovo náměstí No. 317/5.

Dissident Politician and philosopher Václav Benda lived and died at Karlovo náměstí 287/18. There is metal image of his face on the plaque there.

The inventor of the screw press and propeller, Josef Ressel, is remembered at the entrance to Karlovo namesti 293/13, part of ČVÚT. The same university building has a plaque for ČVÚT rector Viktor Felber, who was executed by the Nazis in 1942.

St. Ignatius Church and ČVÚT both have markers for victims of Nazi and communist totalitarianism, and at Karlovo náměstí 500/37 there is a plaque erected in 2015 to remember the victims of bombings in 1944 and ’45. The base of the plaque comes from part of a bomb casing.

The most recent addition is at Karlovo náměstí 555/31 for Croatian writer and journalist August Šenoa, erected in 2018.

The city plans to undertake a large rebuilding of the park in 2025, and plans have already been approved.

Reading time: 9 minutes

Reading time: 9 minutes