An exhibition of little-known works by František Drtikol, an internationally renowned Czech photographer of the inter-war era, sheds new light on one of this country’s greatest, and most enigmatic, artists.

Titled “František Drtikol: From his Photography Archive,” the exhibition at the Museum of Decorative Arts, which will run through November 24, comprises unique photographs not intended for public presentation. The images show the artist’s work with live models, abstract and staged compositions, and reflect his spiritual orientation towards Eastern philosophies.

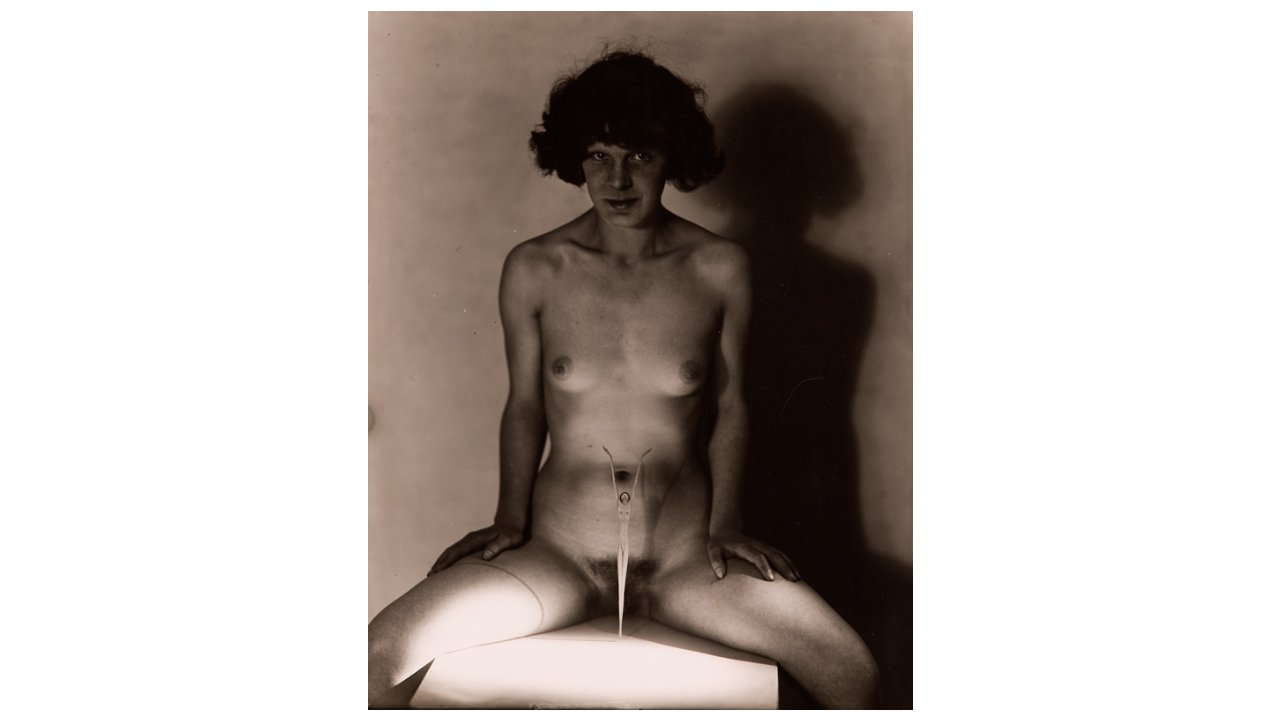

Untitled, 1930

Born in Příbram in 1893, he studied at the progressive Lehr und Versuchsanstalt für Photographie, in Munich, and graduated at the top of his class.

In 1910 he opened a studio in the prestigious Vodičkova ulice in Prague and soon the crème of Czech society was beating a path to his door, drawn by his deeply psychological studies.

“I never merely photographed a person: I tried to give an artistically and psychologically accurate statement about him,” he told reporter Jiří Jeníček in a 1955 interview for the magazine Československá fotografie. “A portrait photographer must emphasize what is essential in the face, dismiss inessential features, tilting the head and body and selecting the lighting accordingly.”

His clients included Czechoslovak president Thomas Garrigue Masaryk, his successor Edvard Beneš, opera singer Emma Destinn, painter Alfons Mucha, politician Maxim Gorki, poet Paul Valery and Indian philosopher and poet Rabíndranáth Thákur.

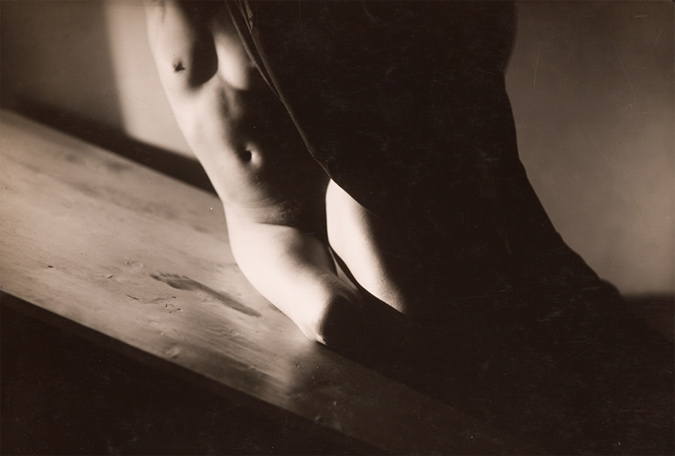

Meanwhile, the art world was fascinated with his nudes: slim, muscular dancers and athletes juxtaposed against simple geometric props of his own design.

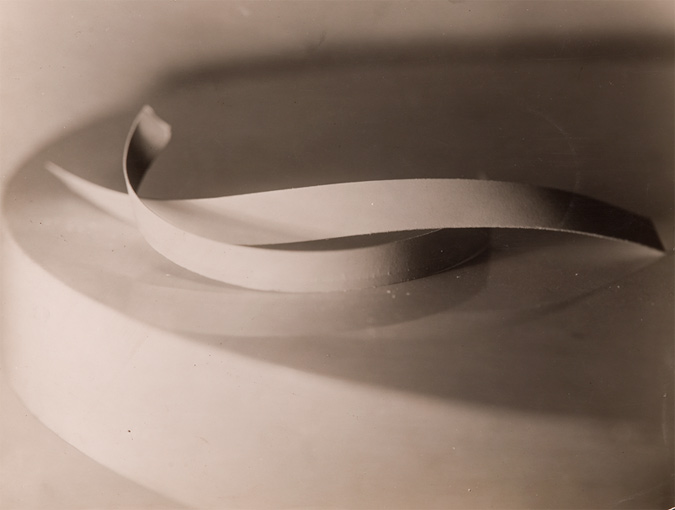

Linie, 1933

“Drtikol created his unique photographic language using three elements: the female body; a few simple geometric shapes and light. These he assembled in various compositions, from which he selected the simplest and most effective one. This is what won him world renown,” said Curator of Photography at the UMPRUM, Jan Mlčoch, who organized the exhibition.

Unlike other photographers, who used the nude as the focus of the image, Drtikol treated it as just another prop.

“I photographed the naked body for its decorative substance, for the play of the muscles in the face and body,” he told Jeníček. “The titles of the photos speak for themselves: Circle and Line, Vertical Wave, Broken Arch or Diagonals…. I tried to express the dynamism between geometric forms and the human body.”

In 1925, he won instant international fame when he won the Grand Prix for a photograph titled The Wave – an arched female nude sandwiched between two stylized wooden waves – in the landmark Art Deco Exhibition in Paris.

For the next ten years his photographs toured the most prestigious photo galleries of Europe and North America, including the Photographic Society of Philadelphia, the Chicago Camera Club, the Cleveland Photographic Society, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Kodak Camera Club in Rochester, the Royal Photographic Society in London, and the Cambridge University Camera Club.

Despite his fame, Drtikol, a devout Buddhist, continually sought to express his quest for the divine. This need intensified in 1929 when, on Wenceslas Square, as he told a student, he attained nirvana. His work became more abstract – and erotic. His famous, Matka země (Earth Mother, 1931), a nude woman with the silhouettes of a man and a woman poised in front of her groin, comes from this period.

Untitled, 1930

In the early 30’s, as portrait orders declined, his business started to fail. Despite the economic hardship, in a series of private studies, Drtikol returned to the nude, but from a gentler angle. He eliminated the geometric shapes and focused only on details. His Snow Wave, a play on the prizewinning Wave, a softly lighted outline of a breast resembling a snowdrift, is typical of this period.

This series, which is the subject of the above mentioned exhibition and is considered to be the pinnacle of his work, ended his photographic career.

“The fact that this very successful commercial photographer created these very costly photos not destined for the public, nor for sale, during an economic crisis which took its full toll on the atelier … was an act of self destruction,” says Mlčoch.

He went bankrupt in 1935. He sold the atelier and moved to a house in Střešovice where he lived quietly, studying and teaching Buddhism and painting his visions of the sublime. Sadly, his paintings were not valued like his photos and he lived in poverty.

By his death in 1961, he had been forgotten – almost. In 1972, thanks to an UMPRUM exhibition, the world rediscovered Drtikol.

Today his works appear in all leading photograph collections. In 2010, the Wave was offered for sale by Berlin’s Kikken Galerie for 400,000 Euro and in 2007 the Snow Wave sold at a Sotheby’s auction for $312,000.

Drtikol himself is known as the founder of the Art Deco photography, and as the patriarch of Czech Buddhism.

It’s difficult to say which would have made him happier.

Reading time: 4 minutes

Reading time: 4 minutes