Zlaté české ručičky a chytré české hlavičky is an old adage in this country, meaning “golden Czech hands and clever Czech heads.”

It allegedly stems from the idea that the Czechs have a propensity for technical ingenuity. Like many old sayings, it actually carries a large grain of truth, as the Czech Republic is a country that clearly punches above its weight when it comes to technological innovation and invention.

Here are just a few of the major scientific discoveries and technological advances made by Czechs that have had a major impact on our lives:

10. Robot – Karel/Josef Čapek

OK, the Čapek brothers did not invent the robot as such, but they have been credited with coining the term that is now routinely used in most languages to refer to all mechanical or virtually intelligent agents that perform various tasks and forms of labor.

The word first appeared inKarel Čapek’s groundbreaking play Rossum’s Universal Robots (R.U.R.), which was in itself a reworking of the Czech Golem myth.

It depicted humanoid workers who were “assembled” in factories to perform various tasks for mankind, but who ultimately rebel against their human overlords with devastating consequences.

Articulating what have now become almost universal anxieties about the relationship between man and machine, the play rapidly caught the public imagination when it was first staged in 1921, and the word “robot” quickly supplanted “automaton” as the term for artificially intelligent mechanical devices.

The philosophical questions Čapek’s play raised about AI are still pertinent several decades later and are also pervasive in popular culture as seen in TV shows like Battlestar Galactica or the cult movie Blade Runner.

R.U.R. may not have actually contributed to the development of robots, but it helped create and sustain the intellectual climate that has evolved alongside advances in the field of mechanical intelligence

As science fiction writer Isaac Asimov, who himself coined the word “robotics”, put it: “Čapek’s play is, in my own opinion, a terribly bad one, but it is immortal for that one word.”

Incidentally, there is evidence to suggest that the word “robot” itself was not actually chosen by Karel Čapek, but was suggested to him by his painter brotherJosef. It comes from the old Czech word robota meaning “forced labor” or “drudgery.”

9. Polarography – Jaroslav Heyrovský

The term “polarography” may not mean much to the average layman.

Indeed, the Oxford Dictionary’s definition of polarography as “the analysis by measurement of current-voltage relationships in electrolysis between mercury electrodes” would not really do much to make the term any clearer to most of us.

Nonetheless, this revolutionary technique devised by Czech chemist Jaroslav Heyrovský in 1922 now has countless useful applications in chemical analysis.

Polarographic techniques, for instance, can be used in analyses to determine the presence of vitamins, alkaloids, hormones, and coloring agents in various substances. Consequently, it plays a vital role in the food-processing industry, toxicology reports, the analysis of drugs and pharmaceuticals, and in detecting the presence of residual herbicides and pesticides in foods and other substances.

It is a field of study that was considered important enough for Heyrovský to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in recognition of his work in 1959, making him only one of two Czech scientists to receive such an honor (the other being Carl Ferdinand Cori).

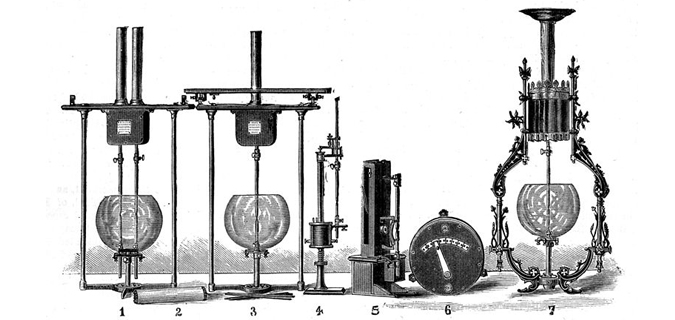

8. Arc Lamp – František Křižík

As one of the fathers of the Czech Republic’s heavy-hitting electrical engineering industry, František Křižík has a number of important technical innovations to his name.

These achievements range from making pioneering railway signaling devices to constructing electric tramway lines and power stations. He is also the man responsible for building the “musical fountain” in Výstaviště, which now bears his name and is still a popular Prague attraction to this day.

Perhaps his most notable achievement, however, is his work on refining the electric arc lamp, which subsequently came to be used around the world for public lighting.

Křižík first designed an electric lighting system for the Austrian entrepreneur Ludwig Piette at a paper mill in Plzeň in 1880. He subsequently presented his “Pilsen Lamp” at the Paris Electrical Exposition a year later and was awarded the event’s gold medal for his efforts. After Paris, his patent was sold abroad and his light was soon being put to use in several countries

His own continuing efforts to promote the idea of electric illumination in the Czech lands resulted in his winning a tender to install street lighting in the towns of Písek and Jindřichův Hradec with his innovative differential arc lamp in 1887.

Although he was not the first to introduce street lighting and his arc lamp was subsequently replaced by more efficient technologies, Křižík’s innovations helped make electric street lighting more viable, thereby contributing to its rapid spread around the world at the beginning of the 20th century.

Arc Lamp Examples

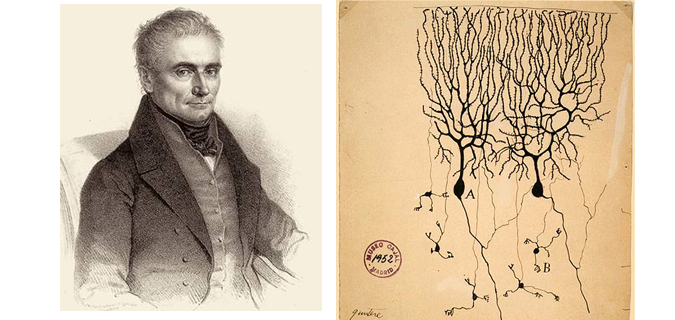

7. Fingerprints, Theory of Cells – J.E. Purkyně

The contribution of 19th-century physician and scientist Jan Evangelista Purkyně to medicine is almost impossible to quantify.

In many ways, he is one of the founding fathers of cellular biology. His pioneering laboratory techniques, including many advances in the use of the compound microscope, led to several major discoveries about the workings of the human body.

His study of “Purkinje fibres” in the heart, which transmit nerve impulses, was one of the many great strides forward that he precipitated in the field of cardiology. He also discovered “Purkinje cells” in the cerebellum, which play a key role in motor coordination.

On a more general level, Purkyně also helped develop a groundbreaking “theory of cells” as the basic structure underlying the human organism.

Besides his many contributions to the somewhat esoteric field of cellular biology, Purkyně also made a massive advance in criminology with his discovery that all human fingerprints are unique and could therefore be used as a form of identification.

In addition to building a primitive zoetrope, Purkyně’s work on eye movement and how human vision functions also presaged the advent of cinematography.

6. Lightning Conductor – Václav Prokop Diviš

Although Benjamin Franklin is widely credited with the invention of the now ubiquitous lightning rod, this life-saving instrument may also have been independently conceived by a little-known Czech priest.

As a scientist and scholar, Václav Prokop Diviš had already constructed several hydro-technical devices and water conduits before he became interested in electricity.

Around the year 1754, he constructed a special “weather machine” aimed at harnessing atmospheric forces in the town of Přímětice, near Znojmo, Moravia.

This consisted of a long metal pole intercrossed with metal bars and grounded to the earth with three conductive cables.

Although Diviš had erroneously intended for his invention to prevent lighting and electrical storms, his correct belief that this device would “suck” electricity from the atmosphere meant that he had effectively built one of the earliest lightning conductors.

Unlike Franklin, Diviš never really got due recognition for his innovation and his conductive pole was even pulled down five years later by angry townsfolk who blamed it for a severe drought in the surrounding region.

Incidentally, Diviš is also thought to have designed one of the first ever electrified musical instruments. the Denis d’or, which could mimic the sounds of several different types of instrument (not unlike a modern-day synthesizer).

5. Sugar Cube – Jakub Kryštof Rad

Visitors to the small Bohemian town of Dačice might be a bit perplexed to see a major public monument there displaying what appears to be a giant sugar cube.

The reason for this is that the first ever cube-shaped sweetener was actually made in the town.

The man behind this now commonplace item was Jakub Kryštof Rad, who was the director of a local sugar refinery in the 1840s.

He is said to have been inspired to come up with the first-ever sugar cube by his wife Juliana. As she and her kitchen staff kept injuring themselves while trying to chop up the unwieldy loaves in which refined sugar was supplied at that time, Rad set about trying to come up with packaging sugar in a more manageable size, which prompted him to design a press for producing sugar in small cubic lumps.

This new sugar shape was a massive hit at home, apparently, and Rad took out a patent for it in 1843. Other countries, such as Prussia, Saxony, and England soon bought a license for producing these newfangled cubes and the rest, as they say, is history.

Not surprisingly, given that Rad originally hailed from Switzerland and the sugar cube first came into being in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, there is some dispute about whether the cube is really a Czech invention.

What can’t be disputed, however, is that sugar cubes first saw the light of day in Dačice, and the monument commemorates this fact.

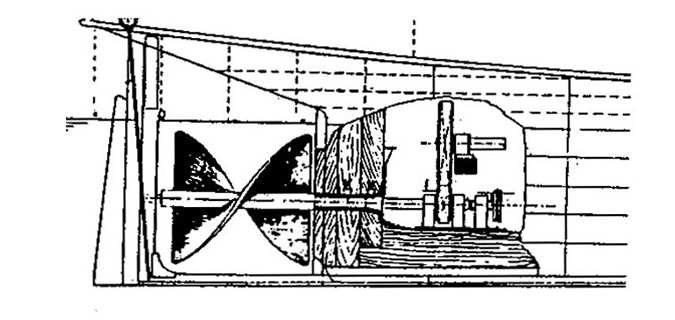

4. Ship’s Propeller – Josef Ludvík František Ressel

Despite being a landlocked nation, the Czech Republic can lay claim to one of the most important inventions in maritime travel – the screw propeller.

This device was the brainchild of the Czech-born inventor Josef Ressel, a forest warden who also happened to have an interest in mathematics, mechanics, and drawing.

His technical talent as a designer meant that he took out a number of important patents during his lifetime, including ones for ball bearings, a rolling mill, and a primitive steam engine.

But it is as the inventor of what is arguably the first practicable screw propeller for which he is best remembered.

It was actually his work as a forester, harvesting wood for shipbuilding purposes, which inspired Ressel to put his mind to improving maritime propulsion.

Although others such as Archimedes and Leonardo da Vinci had pondered the possibility of using screw propellers for propulsion, it was Ressel who first came up with the idea of putting a propeller underwater in order to effectively move boats and ships forward.

In 1826, he applied for a patent for a “never-ending screw which can be used to drive ships both on sea and rivers,”, which usurps the claims of other designers such as Francis Pettit Smith and John Ericsson who came up with similar devices a decade or so later.

3. Blood Types – Jan Janský

Although the American biologist Karl Landsteiner won a Nobel Prize for identifying different blood groups, some of the credit for this discovery can also be given to the Czech scientist Jan Janský.

As a psychiatrist and neurologist, Janský had investigated the possibility of a correlation between blood diseases and mental illness.

Although his research found that no such correlation existed, one by-product of Janský’s work was that he learned that human blood could be classified into four distinct groups.

This finding in 1907 helped pave the way for the ABO blood group system that is still widely used to this day.

Because of the limitations of communication at the time, as well as the fact that Janský’s discovery was ancillary to the aim of his initial research, his findings went unnoticed for many years.

Nonetheless, Janský’s contribution was duly acknowledged by an American medical commission in 1921 when it accepted that human blood could actually be divided into four separate groups and not three as Landsteiner had posited.

Janský is also credited with helping to promote the use of blood transfusions and donations, which continue to play a vital role in medicine to this day.

2. Stanislav Brebera – Semtex

Given its historical role as a world leader in the production and export of armaments, it is not surprising that Czech weaponry has played a major role in many conflicts around the globe.

Perhaps the most famous, or rather notorious, product of the country’s arms industry is the general-purpose plastic explosive Semtex.

Developed by the Czech chemist Stanislav Brebera at the end of the 1950s, it began to be mass-produced in the mid-1960s to supply the communist Viet Cong government during the Vietnam War. (It derived its name from the village of Semtín near Pardubice which was home to the Explosia factory where it was produced).

1. Soft contact lenses – Otto Wichterle

Otto Wichterle is perhaps the most quixotic of Czech innovators. The story of how he used his son’s “meccano” set and the dynamo from a bicycle lamp to develop a process for manufacturing the world’s first practicable soft contact lenses is legendary.

Wichterle had been forced to develop his contact lenses at home in 1961, because the Czechoslovak Ministry of Health had withdrawn funding for his research into a special plastic “hydrogel” which became the base material for his comfortable and ergonomic visual aids that are now used by more than 100 million people all over the globe.

Amazingly, Wichterle is said to have made only a few hundred dollars from his invention, because the Czechoslovak socialist government of the time sold the patent to a U.S. company, which began the mass production of the device.

It was not the first or last time that Wichterle was to be badly treated by an authoritarian Czechoslovak government. By the time he invented his contact lenses, his scientific work had already been disrupted several times as a result of purges by both the fascist and communist regimes.

He was to lose his job as a research director once more in 1969 because of his opposition to the socialist government’s hard-line “normalization” policies, which were implemented after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, even though by that time he was one of the country’s leading chemists with over a hundred patents and dozens of important papers to his name.

Thankfully, Wichterle was to eventually receive at least a modicum of recognition for his work when at the age of 76 he was appointed president of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences immediately after the Velvet Revolution in 1989.

Related articles

Reading time: 11 minutes

Reading time: 11 minutes