A new exhibition titled “Vital Art Nouveau 1900” at the Municipal House shows how art revitalized life and life revitalized art at the turn of the last century.

In the last decade of the 19th century, young artists all over Europe started rebelling against the fine arts academies.

PARTNER ARTICLE

One of the first “secessions” took place in Prague, in 1887, when a handful of artists broke from the Prague Fine Arts Academy by founding the SVU Manes (Association of Fine Arts Manes). In 1892, artists in Munich and Berlin also rebelled. The Viennese Secession, which gave a name to the movement, took place relatively late, in 1897.

These young and angry artists were fighting against the stranglehold state sponsored fine arts academies held on artistic expression.

With a curriculum based on historicism, or the copying of past masterpieces, these institutions – incidentally the greatest foes of the Impressionists – favored highly refined, dramatic, and politically correct historic tableaus.

There was a reason.

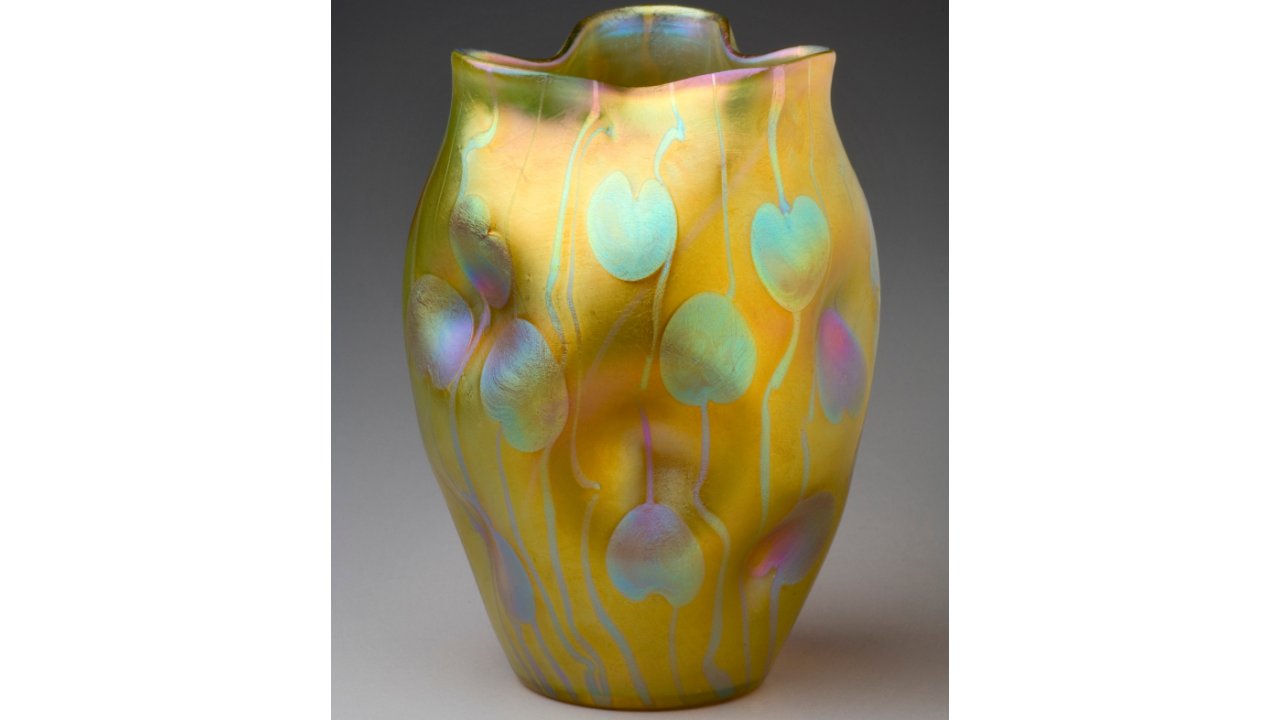

Glassworks painting workshop, 1905

“In the 19th century, a very powerful class of entrepreneurs, very traditional, very mindful of material wealth came into being and started competing with the older aristocratic society. To legitimize itself, it turned to historicism,” says Head Curator at the Museum of Decorative Arts (UPM), Radim Vondráček, who drew upon the institution’s vast archives to assemble the exhibition.

“That’s why you see so many Neo-Renaissance banks around town,” he sighs.

Also known as L’art Pompier (Firemen’s Art), due to the paintings of soldiers wearing fireman-like helmets, academy art was seen as sentimental, clichéd and conservative.

The secessionists longed to create a new style not beholden to the past. For inspiration, they turned to the lavishness of nature and the result was a daring, spontaneous style, a riot of vibrant colors, rounded forms and whiplash lines.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Poster Divan Japonais, 1892

But they took it one step further. Art, they said, is not just for gallery walls, it must be lived. The artist must venture beyond “fine” art, into the realm of everyday, utilitarian objects.

Soon artists were designing everything from teapots to typefont and Europeans were living in art nouveau houses filled with art nouveau furniture, eating from art nouveau plates reading art nouveau books and wearing art nouveau clothes.

According to Vondráček, this instant affinity went beyond mere esthetics: Europeans were yearning to break out of their bourgeois constraints and the Secessionists led the way.

To illustrate this point, Vondráček, has drawn upon upon the UPM’s vast archives to assemble over 400 objects of everyday use, many designed by top artists of the period, including glass by Reneé Lalique, lamps by Louis Comfort Tiffany and furniture by Louis Majorelle.

But he goes beyond mere display. His selection demonstrates how changes in late 19th century society were reflected in art – and vice versa.

Take the bicycle, or rather the image of a woman on a bicycle, a frequent subject of Art Nouveau illustrations.

“In Europe, the bicycle was a symbol of emancipation because it allowed women to travel alone,” Vondráček explains. “The bicycle also caused a change in women’s fashions: sporting apparel started to appear.”

As women became more athletic, they became more health conscious and they realized their clothes were killing them – literally.

Supported by physicians who had traced “female” illnesses such as fainting, weakness and nausea to the corset, they started a “Clothing Reform Movement,” aimed at designing ‘natural’ dresses which copied the curves of the female figure.

The new Parisian style, 1907

“They looked a bit like Empire tunics, free flowing and laced under the bust,” Vondráček says. “They eliminated the need for that medieval torture instrument that permanently deforms a woman’s body … That’s when the first bras, which played a huge role in female emancipation, appear.”

It is no accident, therefore, that a full quarter of the exhibition is devoted to fashion, including the first bras.

There is also a section devoted to toys and children’s books. This is because Art Nouveau artists were the first to start taking childhood seriously.

“Childhood as such was born in the 19th century. Until then, children were seen merely as small adults.

Art Nouveau took toys just as seriously as the design of the Živnostenská bank,” Vondráček says.

The same went for children’s books.

“Yes, they had been around for a while, but a giraffe in a children’s book looked just like a giraffe in a book for adults,” he says. “Art nouveau was the first to consider children’s art as a separate form.”

The great botanical expeditions of the 19th century led to a new fascination with the world of plants, reflected in glass, ceramics, architecture and the gorgeous furniture by French designer Louis Majorelle, among others.

Photography and film were just coming into their own as art forms.

Alfons Mucha, figural scene, 1899

“The change in perception that photos and film caused could be compared to those experienced by our generation in the internet revolution,” Vondráček says.

The exhibition includes photos by Alphonse Mucha and František Drtikol’s grisly “Salome,” as well as film clips and live Prague street scenes from the era.

And let’s not forget the posters of Alphonse Mucha, Toulouse Lautrec and “The Father of the Poster” Jules Chéret.

The invention of the poster was due partly to the introduction of trams. People hurtling along city streets at 20 miles per hour couldn’t read small print fliers, and advertisers needed a larger medium to catch their attention.

In 1867, Chéret used the new four-color lithographic process to create a highly stylized form of graphic art that thoroughly integrated text and image. In 1889, he was awarded the Legion of Honor for creating a “new branch of art.”

And that’s just a fraction of what’s to be seen. The exhibition also includes masterpieces from the landmark Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, self-service multimedia tablet presentations, 3D scans of Art Nouveau objects and online access to digitized collections of prominent European institutions.

In short, the exhibition, which will run through December 31, 2015, is an afternoon well spent.

**

Lead image: Jules Chéret, Thèâtrophone, 1890

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes