Residents in Prague have no doubt noticed brass-colored stones in front of buildings. These paving stones, called Stolpersteine, are part of an international project to remember victims of Nazi persecution.

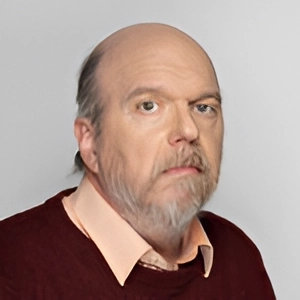

A new book called “Prague’s Stolpersteine” with the subtitle “Stumbling Stones Defiant in their Memory” has just been published in English. The author, a British man named Trevor Sage, has made caring for these stones his passion for the past several years. He can often be found cleaning the stones so the names and details are legible, and the brass looks polished. The book is available at Oxford Bookshop at Korunní 65 and at Oko! Bistro at Chopinova 6, both in Prague 2.

Stolperstein translates from German as “stumbling stone.” The plural is Stolpersteine. They are part of an art project conceived by German artist Gunter Demnig in 1993.

“The stones memorialize people persecuted or murdered by the Nazi regime between 1933 and 1945. Gunter made the first Stolpersteine in Berlin in 1996. Today, there are more than 88,000 in 26 countries throughout Europe,” Sage said at the book launch, held at the British Embassy in Prague.

Another book launch will be held at Oko! Bistro on Friday, Dec. 3, at 5 pm. That event is open to the public.

“Today there are 466 Stolpersteine in Prague and this number increases by about 50 every year,” he added.

The stones were first introduced to the Czech Republic in 2008 by members of the Czech Union of Jewish Youth. Since 2018 the installations have been overseen by Prague Jewish Community head František Bányai and historian and tour guide Hermína Neuner.

The rather slow expansion of the project is because Demnig still oversees the creation of all of the stones not just for the Czech Republic but for all of Europe.

The stones can be found in front of the buildings where victims of Nazi persecution lived before they were transported to concentration camps or met similar fates. The stones have the name of the person plus the date of birth, the date that the person was transported to a camp, and the place and date of death if known.

After creating a website to map out the stones in Prague, with details about whom the stones represent, Sage decided the information needed to be in book form. He used crowdfunding as well as a grant to finally be able to publish his book.

The fundraising was so successful that roughly twice as many books were printed as originally planned, and half of them are already gone, either to people who participated in the fundraising or to pre-sales.

“Most of the people commemorated in the book were transported on the many transports from Prague, a journey from which the vast majority would not return,” Sage said. The first transports of Czech Jews from the Praha-Bubny rail station to the concentration camp at Terezín took place 80 years ago on Nov. 25, 1941.

Sage’s involvement with the Stolpersteine project was by chance. “Stolpersteine were first pointed out to me on a tour of Prague’s Jewish quarter. I was told they are known in Czech as stones of the disappeared. This phrase struck me, as I could see many of the inscriptions were difficult to read. The person’s name was quite literally disappearing from view,” he said.

At first, he was reluctant to get involved.

“Although I felt an urge to clean the stones, as a foreigner in my adopted home I didn’t feel it was my place to do so. However, I was inspired by a story of a gentleman in Salzberg, Gerhard Geier, who like me isn’t Jewish yet he cleaned all 288 Stolpersteine in his city,” Sage said.

“So on the 8 of June 2018, motivated by the work of Gerhard, I started cleaning Prague Stolpersteine. Little did I know that that day would start a journey leading to me standing here in the British Embassy and launching this book,” he said.

He didn’t make any announcements when he started his cleaning project. It was simply a personal task.

“After a few days of cleaning was stopped by Jitka Hejtmanová who asked me what I was doing. This was the first time anyone had spoken to me while cleaning the stones. And I welcomed the opportunity to explain my project. Jitka then asked if she could take a photo of me and post about my project on Facebook,” he said.

“The response to Jitka’s post was astounding. So many people were interested in my project that I decided to set up the Stolpersteine Prague Facebook page. I posted photos of the stones before and after cleaning so everyone could follow my progress. To date, the page has more than 3,000 followers,” he said.

The amount of interest led him to believe he could take the project further. While the stones have the name and some dates, they don’t really tell you who each person was.

“I knew behind every name there was a story waiting to be told. I am neither a historian nor a researcher, but I wanted to find out what I could about the person named on every stone,” he said.

Using databases and other records he was able to find many photographs of the people and more details about their deportation and fate.

“I felt this information should be easily accessible to anyone. So with some help, I created an online map of the stones’ locations. I added photographs of the person and links to the online information about the deportation,” he said.

He got information from relatives when new stones were installed, and more people started to contact him with information and stories about their loved ones.

“In May last year I decided all the information needed to be brought together in a single publication,” he said.

Hermína Neuner did not attend the book launch due to the pandemic, but she sent a short speech. She pointed out that for the family members of Jewish victims, the stones often replace the nonexistent graves of their relatives. “At the same time with their existence in public space, the stones also serve the whole society as they recall the tragic fates of people who once used to be our neighbors,” she said.

She added that the installation of each stone is a long and complex process that involves archival research, communication with descendants of the victims, concerned people, and relevant institutions.

“The installation itself is the end of the entire process but in fact it is the very beginning of its goal. The stones must be taken care of in order to serve their purpose. And Trevor is the one to make it happen in Prague, she said, adding her thanks.

The stones themselves have only a thin piece of metal on top of a small concrete block the size of a standard paving stone. Initially, a few were stolen as thieves perhaps thought they were solid blocks of metal that could be sold to metal collection points. The stolen ones have been replaced, and now very few are ever damaged or stolen as the word seems to be out that they cannot be sold.

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes