Controversies is a journey through the history of photography and photographers, prepared by the Musee d’Elysee in Switzerland and showing at the Rudolfinum until November. Each of the 80 photographic exhibits is ‘controversial’ in some sense, either in its subject matter or the manner in which the image was shot, retouched or published.

The exhibition is arranged around some key themes: the recognition of photography as a viable art form worthy of intellectual property protection, the role of photography in news reporting, the interplay between a democratic society’s demand for a free press versus the individual’s desire for privacy, the ethics of altering or retouching photographs, and the delicate area of photographing child nudes.

PARTNER ARTICLE

The exhibition explores the grey area between what are considered normal and accepted photographic practices in Europe and the United States, and the downright controversial. Controversies raises questions, promotes debate and prompts thought and discussion throughout.

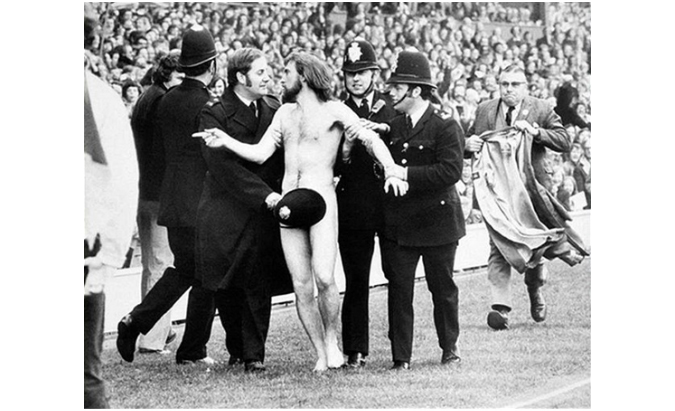

Some of the exhibits will be familiar to many people: The Kiss at City Hall (Doisneau, 1950), The Twickenham Streaker (Bradshaw, 1974) and The Little Girl of Trang Bang (Ut, 1972), although the reasons for their controversial nature may not be so well known. Other images were new to me, but well support the clear themes running through the exhibition.

Ian Bradshaw (*1943) – The Twickenham Streaker (1974)

Several of the images are shocking and some make difficult viewing: photographs taken by a British Army photographer at Bergen Belsen (1945) and the horrific scene captured by Carter in Sudan (1993) depicting a starving child trying to reach a feeding centre, alone and close to death, watched by a vulture.

One of the themes central to Controversies is the history of photography; the legal and intellectual battles that took place in Europe and the US that resulted in photography being recognized as an art form worthy of protection (such as the court case surrounding Sarony’s Portrait of Oscar Wilde, 1882). A number of the photographs on display were once (or, in the case of Korda’s image of Che Guevara (Cuba, 1960), still are) the subject of intense court proceedings concerning copyright, and the rights of photographers to be credited properly for their work.

Controversies also considers the purpose that some photographs serve in a wider context. Photographs are often used as hard evidence of facts and events. The Bergen Belsen photographs were used at the Nuremberg Trials as evidence of Nazi atrocities. On the other hand, Frentz’s photographic depiction of concentration camp workers at Mittelbau-Dora (1944) were composed and published in order to deliberately mislead and conceal the true horrors of the Nazi camps.

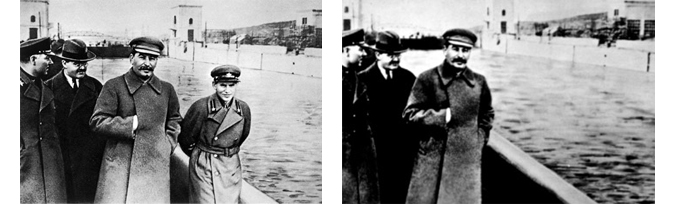

Similarly, the ‘retouching’ of photographs is discussed. Whilst the retouching of images, facilitated today by digital processing, can sometimes be for pure vanity’s sake or as part of a child’s prank (Wright and Griffiths – Fairy Offering Flowers to Iris, 1920), there is a darker side to such practices. Retouching allows less scrupulous individuals or organizations to re-write history. This is aptly shown by the ‘before and after’ reproductions of the image of Stalin walking with (and then ten years later, without) the disgraced Internal Affairs Commissioner, Nikolai Yezhov (Anonymous, 1930s). After he fell from favor, Yezhov was quite literally removed from the Communist Party’s history, including from its photographic records. The party controlled every aspect of life in the Soviet Union and used all the tools at its disposal to do so.

Kliment Voroshilov, Vyacheslav Molotov, Stalin and Nikolai Yezhov at the shore of the Moskwa-Wolga-Channel

Less sinister but equally intriguing is the retouching of Lipnitzki’s portrait of Jean-Paul Sartre (1946). The image was later doctored to remove a cigarette from Sartre’s hand. The photograph was published in order to advertise a Sartre exhibition, which opened sometime after the French anti-tobacco legislation came into force. It was apparently impossible to find a photograph of Sartre without a cigarette in his hand. The exhibition organizers took the pragmatic approach of altering the image, but faced widespread criticism for doing so. We mainly accept re-touching (especially of celebrities) as a ‘given’. But when is acceptable, if ever? To what extent can an audience rely on what it sees?

The ethical debate of the interplay between photography and responsible, informative journalism is central to the exhibition. Faas’s Bangladesh (showing prisoners being tortured and killed with bayonets) and Carter’s Sudan are two images where this debate has been heated in the past, and questions still remain today. Do professional photographers have a moral duty to intervene, or is it enough to take a picture of events for public distribution. How, or even should, you depict the horrors of human suffering?

Another theme running through the exhibition, which still dominates public debate and law courts today, is the interrelationship between the demand for a free press and the individual’s right to privacy. I found the image of Bismarck on his death bed (obtained when photographers Priester and Wilcke (1989) broke into Bismarck’s private room in his final hours), to be in very bad taste and the ultimate invasion of privacy. The image was not published until 1952. Nowhere in recent history has the intrusion of the paparazzi been so starkly demonstrated than in the final portraits of Lady Diana (Langevin, 1997), although even Controversies stopped short of including the images of Lady Diana in the wrecked car (which were, controversially, published in 2006 by an Italian magazine).

The fascinating topics discussed in this exhibition are well supported by wonderfully able and innovative curatorship. Each image was accompanied by informative text (all provided in Czech and English), available in paper form for visitors to pick up and bind into their own take-away exhibition guide. It was the first time I have ever seen this ‘do it yourself’ approach, but it worked incredibly well. Visitors can read the text on the spot and may then choose to include it in their own small binder (provided on entrance), or leave it if it is not of interest to them. At the end of the exhibition I had my personal exhibition program, which was about 1cm thick and full of information about the images I found most interesting.

Taken together, these photographs and the adept curatorship accompanying them introduce some of the key themes surrounding photography both as an art form and as a political, business and journalistic tool. It also tells the stories of photographers: collectively, in pursuit of copyright protections, and personally – Carter for example, killed himself soon after winning the Pulitzer Prize for Sudan.

Kevin Carter (1960-1994) – Sudan 1993

Whether or not visitors find particular images ‘controversial’ will come down to their personal values. For example, I found the doctoring of the Stalin/Yezhov image (and other examples of politically sensitive retouching) to be controversial, if not surprising. I did not particularly object to the changes made to Sartre’s portrait, however. This is a personal opinion – others may consider it just as important that photographs of non-political figures are true to the social context in which they are taken (i.e. one in which Sartre’s smoking was acceptable), rather than the one in which they are published.

There were other areas where it is hard to reach a firm conclusion. After Sudan, Carter came under intense criticism. The St. Petersburg Times said: “The man adjusting his lens to take just the right frame of her suffering, might just as well be a predator, another vulture on the scene”. However, in my opinion it is images such as these that raise, to a level that words generally fail to reach, awareness of human suffering in certain areas and the need for international aid.

Controversies is one of the most engaging and thought provoking exhibitions I’ve seen and I would encourage anyone with even a remote interest in photography, copyright law or modern history to make time to see it.

Controversies is open until 13 November 2011. It is also supported by a number of lectures related to copyright laws and controversies in Czech photography, details of which are available on the Rudolfinum website.

Tickets: Full 130 CZK, Reduced 80 CZK

Galerie Rudolfinum, Alšovo Nábřeží 12, Prague 1

http://www.kontroverze.eu

http://www.galerierudolfinum.cz/en/

Tue.–Wed., Fri.–Sun.: 10–18 h.

Thursday: 10–20 h.

Monday closed

Reading time: 6 minutes

Reading time: 6 minutes