I borrowed a camera from a friend, just to try it out. I took the tram to the end of the line, to what I thought was the edge of town, but I found that the edge, border or end was farther, much farther, away. I’m still using that camera – and searching for the edge.” – Tomáš Novák, photographer, from an introduction to his photo essay on Prague’s peripheries.

Tomáš Novák’s photo essay on the peripheries of Prague, on display through the end of January in Old Town Hall, makes you want to cry. It shows a world, beautiful yet forlorn, poised precariously on the edge between the past and the future – a world that could still be saved – now.

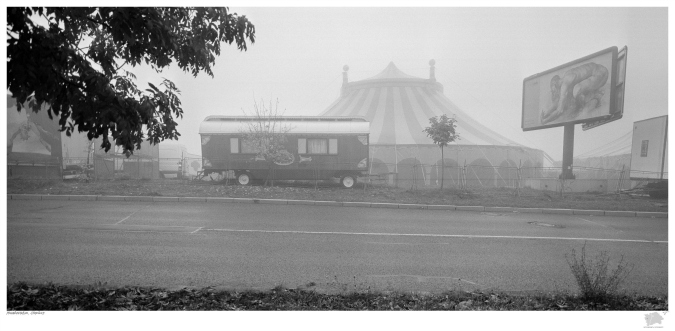

Novák calls the outskirts of the city Prague’s compost heap.

“You don’t put your compost in the middle of your garden you put it at the edge and you heap clutter around it. That’s how we’re treating the edge of town,” he says. “You see it most on the big access roads. But on the side roads there’s some incredible scenery – which we are capable of destroying in a matter of years.”

He should know.

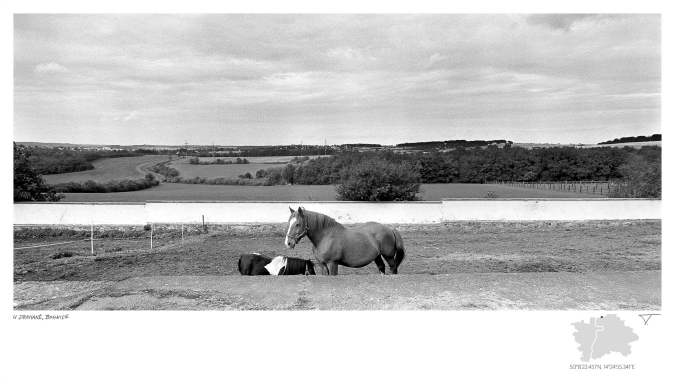

U Drahaně, Bohnice

The art director of the economic weekly Euro spent his weekends last year scouring the edges of town, toting a tripod and panoramic camera, looking for subjects for his project, which won the prestigious Grant of Prague for 2012

“I would take a bus to the end of the line and walk to the next end of the line,” he says. “The thing is, you had to keep coming back. For example, if I knew that in the village of Ujezd the light was going to be right at 9 a.m. tomorrow, and the forecast was good, then I had to be in Ujezd at 9 a.m. Then, sometimes, the light wasn’t right anyway, or the composition was all wrong – but you don’t figure that out until you develop the film.”

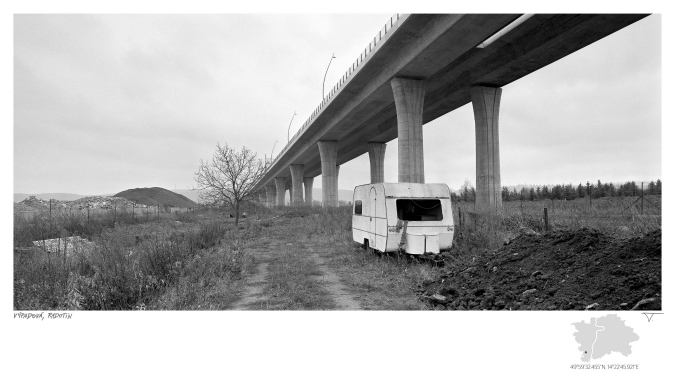

Yes, film. In this digital age, Novák insists on using an analog camera and 6 x 12 centimeter film (i.e. each negative frame measures 6 x 12 centimeters). Though it allows him to take pictures so clear you can see individual sheaves of wheat a mile off – something digital is hard put to do – it translates into six exposures per film. He doesn’t see this as a bad thing.

The village of Ujezd

“You have to think through every click, adjusting your pace accordingly. You don’t do that with digital. There you click faster than you think – with corresponding results.”

In spite of his painstaking care over compositions, his main goal was documentary, not artistic. That’s why every photo has its own map and precise GPS coordinates, allowing future generations to go back and note how they changed, for better or for worse.

“You should be able to see what terrible – or not so terrible – things we committed there,” he says. “I don’t want to be overly artistic, just to document the present reality. To take banal, ordinary photos which will become important over time, when the landscape changes.”

Radotín

But his photos are anything but banal.

Outside the village of Vinoř, a tiny baroque station of the cross stands in the middle of a vast wheat field under a sky full of rolling clouds. Nearby is a copse, home to deer who venture out at night to graze. Far off, barely to be seen, a giant smokestack pokes its head over the horizon like the first lance of an advancing army.

In the suburb of Modřany, a few hundred meters from the highway, ducks swim in a flooded park among benches and trees stretching their stark, bare branches up to the looming sky.

Near the ancient village of Slivenec, a wooden outhouse with a heart carved above the door stands a few feet away from a concrete wall behind which a gargantuan satellite dish servicing a posh, half-built housing development turns its face skyward like some monstrous sunflower.

Mladoboleslavská, Vinoř

The hidden message is a plea to tread lightly.

“These peripheries are changing the fastest,” he says. “Prague is growing outwards. When you have a construction project in the center, there’s always a huge humbug about it. But on the edge it hardly gets noticed, except for some 50 locals fighting, unaided, against some warehouse or factory. Usually it ends tragically. And that’s how we behave toward everything.”

Mukařovský, Stodulky

“We like looking at photos from times past and we barely realize that, at the time they were taken, they were just ordinary reflections of reality,” he writes. “Time will show if my efforts made sense. I’m convinced they do because every second is past and it’s only up to future generations to decide if they will deal with their past as badly as, in many cases, we have with ours.”

**

Prague Peripheries at Czech Press Photo

now through Jan 30, 2014

Old Town Hall

Prague 1

http://www.czechpressphoto.cz/en/

Reading time: 4 minutes

Reading time: 4 minutes