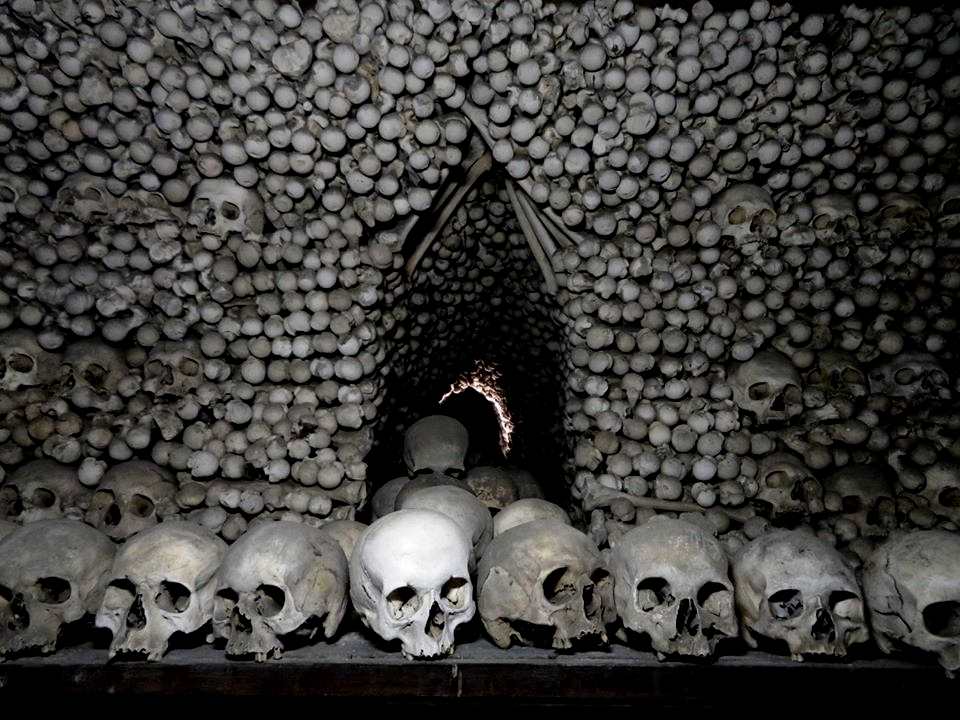

Several mass graves have been found near the Bone Church in Kutná Hora, some 85 kilometers east of Prague. This, in addition to the ossuary and previously known graves, makes the location the largest burial ground not only in the Czech Republic but also in Europe.

The graves, from victims of plagues and famines, were found during the ongoing renovation of the grounds of the Cemetery Church of All Saints, part of Kutná Hora’s UNESCO World Heritage Site. The church is technically in Sedlec, a suburb adjacent to Kutná Hora.

There were 34 newly discovered mass graves containing the bones of approximately 1,300 people who died in a famine in 1318 and a plague in 1348.

“It’s unique in Europe. Previously, the largest number of plague victims was in London, with around 700 victims, so we have a little more,” archaeologist Jan Frolík told news server Novinky.cz.

The extensive

renovations are intended to correct structural problems in the Church

of All Saints, which has been leaning due to the unstable soil. There

has been deterioration of support pillars and cracks in walls. The

large pyramids of bones in the famous ossuary also need to be cleaned

to prevent damage. One of the four pyramids has already been

dismantled.

A deep trench was

dug around the church so builders could reinforce the foundation,

insulate it from water damage, and improve ventilation.

The bone pyramids

are filled with debris with bone fragments. The fragments will be

buried in the cemetery, and the rest of the bones and skulls are

being restored and preserved by anthropologists. The pyramids will

then be rebuilt.

The ossuary at the church, a basement filled with bones placed in decorative patterns, was the Czech Republic’s 17th most visited attraction in 2018, with 426,900 visitors, and is likely to have more than half a million this year.

Changes will come next year, as photography will be banned unless someone obtains prior permission. The church rector, Petr Tobek, wants to restore a dignified mood. Also, some people have been coming into contact with the bones to take selfies, and this risks damaging them.

The entry and exit

route will also be changed after the renovations finish in 2022, so

people can see some of the actual underground area, with clay walls,

after seeing the room with the bones. The underground corridors will

have space for exhibitions and souvenir sales.

The renovations began in 2014, and are being paid for by the church parish out of admission fees. It should coast approximately 45 million CZK.

The church cemetery became a popular place to be buried because it contained a handful of dirt brought back from the Crusades. Bohemian King Otakar II sent a Cistercian monastery abbot named Jindřich to Jerusalem in 1278. He returned with dirt from Calvary, the hill where, according to Christian tradition, Jesus Christ was crucified. The abbot spread the dirt into the cemetery.

People back then

believed relics had almost magical powers to connect people to the

spirit realm. So a cemetery with a connection to Jesus would have

been seen as a direct highway to heaven.

After word spread

that the holy soil was there, the cemetery became one of the most

popular places to be buried. The cemetery expanded as much as it

could, but was always at its capacity.

Around 1400, a

church was built in the middle of the cemetery. The lower level

chapel was designed as a place to put the excess bones from mass

burials or from graves that were no longer kept up.

The upper part was

renovated in the Baroque style between 1703 and 1710, based on a plan

by Jan Blažej Santini Aichel.

The noble Schwarzenberg family in 1870 hired woodcarver František Rint to organize the bones. With the help of his family, he arranged them into designs including chandlers and a coat of arms, and made the bone pyramids. It is estimated that the bones of some 40,000 people are in the chapel.

Reading time: 3 minutes

Reading time: 3 minutes