Mattoni is almost synonymous with mineral water in the Czech lands. There is no greater indication of this then the fact that people order a ‘matonka’ when they want a mineral water, irrespective of the brands available. The brand has its roots in the nineteenth century craze for spa therapy. But while the bottled water is still available and thriving, the town of Kyselka, where the spring is located, has suffered from years of neglect.

Taking the Waters

The north of the Czech Republic is especially abundant in mineral springs. If you look at a map of the spas’ locations, you will see a band of them trailing across the north then dipping south through Moravia. It was only a matter of time before a local spa culture developed.

The use of mineral water for medicinal purposes has a long history in Europe, and the Czech lands are no exception. The first record of the spring at Kyselka is from 1522. It’s conceivable that local people may have used these springs years or centuries before they were officially discovered.

In 1829, Wilhelm von Neuberg developed the town into a spa complex. Under his patronage, a restaurant and a pavilion were built above the spring. The water’s fame spread, and in 1852 King Otto of Greece paid a visit. Apparently he had 450 jugs of water sent to Athens. He made a return visit a year later. The spring, called Otto’s Spring (Ottův pramen), is now named after him.

Success Flows

The spring started to modernize and to develop when it was leased by Heinrich Mattoni in 1867. He set up a bottling plant there in 1868 and by 1896, over 300,000 bottles of Mattoni were being shipped around the world.

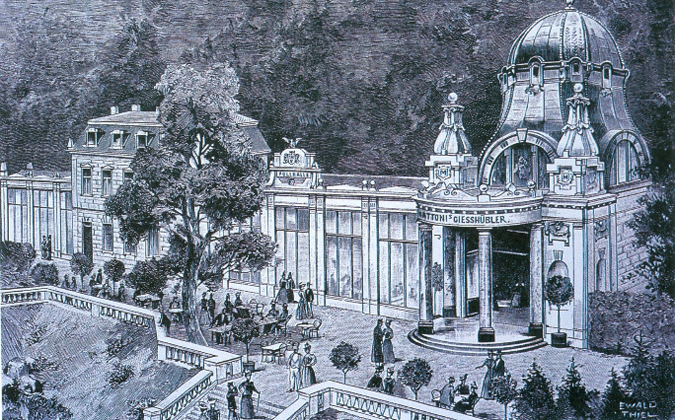

The resort itself flourished under his ownership. The Chapel of St. Anna was completed in 1884. It is said Mattoni came here to pray for his sick daughter Kamilka. An inhalation pavilion was opened in 1885 and a new colonnade was opened in 1901.

The colonnade was designed by Karl Haybäck, who designed a number of buildings in Vienna and Karlovy Vary. While Haybäck is not exactly a household name, he has been praised by Austrian architectural critics for the individuality in his design, which undoubtedly lent the town its ornate and picturesque character.

Mineral Wealth

The medicinal benefits of bathing in or drinking mineral water have long been believed. The treatment has been credited with treating poor digestion, problems with the gall bladder and improving blood circulation. One spa from the nineteenth century even claimed that mineral water was a cure for obesity.

You can see the mineral content of Mattoni here. Interestingly, the calcium and magnesium content is given as higher on the Czech page. It is different again on the Russian page. Compared to other Czech mineral waters, Mattoni has quite high levels of trace elements. It comes somewhere in the middle of international brands.

While the health benefits are not as widely accepted by the medical fraternity today, mineral water is clearly a part of Czech culture and history. It retains a strong association with luxury and fine dining. Mattoni is without doubt one of the best known of these brands. However, as the history and current protests show, you can take the water from the town but perhaps the town can’t be taken out of the water.

The Otto Spring with a new colonnade in 1902

Decline of Kyselka

The rise of mass consumer society inevitably impacted upon the European tradition of visiting a spa. The nineteenth century was clearly a boom period and almost all the spa complexes date from this time. Spas were where the upper crust to mingle and be seen while curing what ailed them. Bottling the water meant it could be enjoyed without a lengthy and costly stay. By the time of his death, Mattoni’s plant was exporting 10 million bottles, but patient numbers remained in the hundreds.

Over time, the town attracted a more diverse group of people. Some of the buildings were used for other purposes; one of the pavilions became a cinema and the complex was used as a children’s hospital in the 1970s. The construction of schools in the Radošov section further changed the character of the town away from an exclusive resort.

The water still flowed. Západočeská zřídla, the state-run company, bottled the water from Kyselka from the sixties through to the eighties; the plant’s output increased from 9 to over 13 million liters of water during this time. But the resort’s heyday was long gone. After the revolution, there was a failed attempt to privatize the facilities. The spring was later bought by Karlovarské minerálni vody a.s., who now sells Mattoni today.

Saving the Spa

Despite this decline, Ing. Martin Kadrman, from the Association for the Protection and Development of the Cultural Heritage of the Czech Republic, sees a reason to save the town because of its unique architecture. “It will not only be a loss to the Czech Republic, but a loss to Europe as well.” To achieve this goal, the association started the initiative Save Spa Kyselka.

Kadrman acknowledges that restoring spa culture in Kyselka does not make sense at this time, when the state does not support spa treatment. For him, it is a ‘what-if’. “At this moment, it is imperative to protect the buildings from further devastation. That is priority number one.”

Kadrman added that Karlovarské minerálni vody a.s. hasn’t spent a single crown on repairs in the twenty years of ownership. “They don’t have any interest in cultural heritage,” he said.

The initiative has obtained 40,000 signatures, and has gained support from a number of high profile Czechs such as the musician David Koller, author of Alois Nebel, Jarolsav Rudiš of the music group Tatabojs, and model Agáta Hanychová. Hanychová was even in a clip for the campaign, which has since been brought down for infringing upon Karlovarské minerálni vody’s copyright.

The company has not been pleased with the negative publicity. In an interview with iDnes (in Czech), the director of Karlovarské minerálni vody, Alessandro Pasquale, refuted claims that his company was not interested in protecting the town’s heritage, saying reconstruction of the Stallburg Building and Löschner’s Spring Pavilion will happen in October, providing approval is given. He has also used the interview to level his own accusations at the association, saying they misused the petition and they don’t have an interest in finding a solution.

Easy manual work with electronics - start 8th Jan

🌟 Customer Care Specialist FR – Prague 🌟

The issue has become heated at times. During president Klaus’ visit, Kadrman called Pasquale “dobytek” (cattle), the equivalent in this context to calling someone an animal. Pasquale retaliated by slapping Kadrman, an image caught on film.

Dr. Stanislav Burachovič, a historian with the Museum of Karlovy Vary, has a much more sanguine approach to the issue. “It would be better to save half of the town than bulldoze all,” he said. The cost and what he describes as the terrible condition of many of the buildings, ruined by rain and snow over the years, are major impediments for full restoration.

With opinions so divided, it seems an agreement will be a long way off. For the time being, Mattoni remains a household name, though maybe not in the way Karlovarské minerálni vody a.s. wants.

Should the town of Kyselka be saved?

Related articles

Reading time: 6 minutes

Reading time: 6 minutes

Polish

Polish

Swedish

Swedish

Norwegian

Norwegian

Danish

Danish