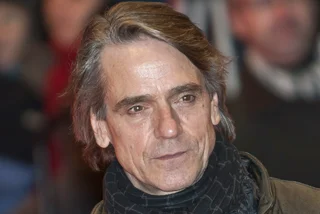

The Munich Agreement, which gave part of Czechoslovakia to Adolf Hitler in 1938, is the subject of a newly released film now streaming on Netflix. “Munich: The Edge of War,” starring Jeremy Irons as British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, debuted on Jan. 21 and is already in the top 10 in many countries, including the Czech Republic. It has garnered good reviews, with an 84 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes. It does, though, play a bit freely with historical facts.

The film is fiction, based on a popular spy novel by Robert Harris. The main thrust of the story is two made-up characters, minor players in the Munich meeting delegations, fiddling around with secret documents and guns and whatnot, all right under the noses of Hitler and his elite bodyguards. This moves the film’s focus away from any discussion of what the meeting is actually about, though Czechoslovakia is at least mentioned a few times.

In September 1938, the leaders of Britain, France, and Italy met with Nazi leader Hitler in Munich to try stave off a large European conflict. Hitler was demanding territorial concessions, and the other leaders were willing to make them, especially since the land they were giving away was not their own.

Representatives of Czechoslovakia, which was being carved up, were not invited to the conference. The Czech press in 1938 referred to it as “Mnichovská zrada,” the Munich Betrayal, a term that is still widely used.

History remembers Chamberlain in particular as a poor statesman who caved in too easily and got little in return for his concessions, save for empty promises. World War II would break out 11 months later, and the Nazis were by that time in control of Czechoslovakia’s heavy industries, which produced tanks, planes, and ammunition.

“Munich: The Edge of War,” though, tries to paint Chamberlain as a brilliant strategist who planned to somehow use the Munich Agreement and another non-aggression agreement to back Hitler into a corner. Ceding land in Czechoslovakia is made out to be something like sacrificing a pawn in chess so you can take the queen a few moves later.

One of the film’s main characters does raise questions about the plan. Minor British Foreign Office clerk Hugh Legat (played by George MacKay of “1917”) suggests to his boss that Czechoslovakia should at least be included in the talks. His boss tells him not to interfere in things above his station. Later, Legat takes his concerns directly to Chamberlain and is just as quickly shut down. He serves only as a sounding board for Chamberlain’s opinion that the Munich Agreement is a great strategic move.

Harris, who wrote the 2017 novel that inspired the film, is best known as the author of the what-if novel “Fatherland,” speculating about what the 1960s would have looked like if Germany won. It became a popular HBO miniseries shot, by the way, on Czech locations.

A similar Harris what-if novel titled “Archangel,” about a group of Stalin loyalists trying to stage a coup, was made into a mediocre film starring Daniel Craig. Harris’s more serious efforts include “The Ghost,” which was adapted into “The Ghost Writer” by director Roman Polanski. It makes serious allegations against a prime minister closely modeled on Tony Blair.

Director Christian Schwochow tries to make “Munich: The Edge of War” look more like a historical dramatization than speculative fiction. Titles cards at the end describe the aftermath of the conference, for example, in a way that gives weight to the view that Chamberlain was a strategic mastermind.

Jeremy Irons is one of the most likable actors, even when he plays villains. He does create a charismatic upper-class politician. And he always exudes an air of intelligence. When he explains his master plan, it sounds credible enough. But that doesn’t make it historically accurate. For comparison, the real Neville Chamberlain can be seen in a 1938 newsreel here as he leaves for the Munich conference.

The casting of Hitler is a bit more problematic. Ulrich Matthes, even with the distinctive haircut and mustache, looks little like the historical figure. He is too old for the part by a decade, and too thin of build and hollow-eyed. The real Hitler in all photos and film footage has a focused demeanor, with an engaging stare and broad shoulders. Matthes, unfortunately, is one of the poorest Hitlers in recent memory, and there have been many.

The script also makes Hitler into a bit of weakling, having to borrow someone’s watch and then make a public joke out of having to return it. The few times he talks he seems like a petty whiner, not someone in absolute control over a nation. The weak Hitler though only serves to boost the idea that Chamberlain was the stronger negotiator.

Matthes did much better in the 2004 film “Downfall” cast as Joseph Goebbels, whom he much more closely resembles.

The cloak and dagger plot, for what it is worth, does have its moments of suspense. George MacKay turns Legat, the clerk who is forced to operate far outside his comfort zone, into an everyman that the audience can sympathize with. His German counterpart, another clerk played by Jannis Niewöhner, does equally well at racking up some tension.

But that doesn’t fully compensate for the overall revisionist history of the film as a whole. While “Munich: The Edge of War” has earned mainly positive reviews, a few news outlets have noted the film’s agenda regarding Chamberlain. The Independent has accused the film of “posh washing,” trying to make a hero out of a failed historical Tory leader at a time when Britain is led by another struggling Tory prime minister, Boris Johnson. The New York Times calls the film “as a feature-length attempt to glorify Neville Chamberlain.”

For a more Czech perspective on the events leading up to the Munich Agreement, the 2017 film “A Prominent Patient,” known in the Czech market as “Masaryk,” shows the response of Czech politicians and diplomats at the time. The film has its flaws, in particular a tendency toward melodrama, but does convey the urgency surrounding Czechs being blocked out of controlling their own fate.

Another film that takes a more avant-garde approach to the topic is Petr Zenkla’s 2015 comedy “Lost in Munich” (Ztraceni v Mnichově). It revolves around a 90-year-old parrot who used to live with Édouard Daladier, who represented France at the Munich meeting. The parrot still repeats phrases related to the time. A journalist tries to make a film about the parrot but is not successful due to the empty promises of would-be backers. The failed parrot documentary is a broad parable about the failed efforts at Munich to create peace.

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes