Anyone with some knowledge of Czech history knows Vratislav Karel Novák’s giant metronome on Letná Park wasn’t always there. Even if you didn’t know exactly what stood there in the past, as soon as you see the bright red mechanism, it seems so out of place with the rest of the cityscape that you wonder what was there before. The answer, which may be received with shame or scorn or a mixture of the two, is that there once stood the largest statue of Joseph Stalin in the world.

An Unexpected Winner

The decision to erect a monument to Stalin was made in 1949, soon after the communists took power. The design would be decided by competition, and all sculptors at the time were required to enter. “It was a political duty to take part in the contest,” said Josef Klimeš, who would be one of the team which worked on the monument.

The winner was Otakar Švec. At the time, he was not considered a serious contender. This son of a pastry chef, Švec’s most famous statue was “Sunbeam Motorcyclist”, which incidentally sold for a little over £139,000 last year at Sotheby’s. After competition, his name would be forever attached to the Letná monument.

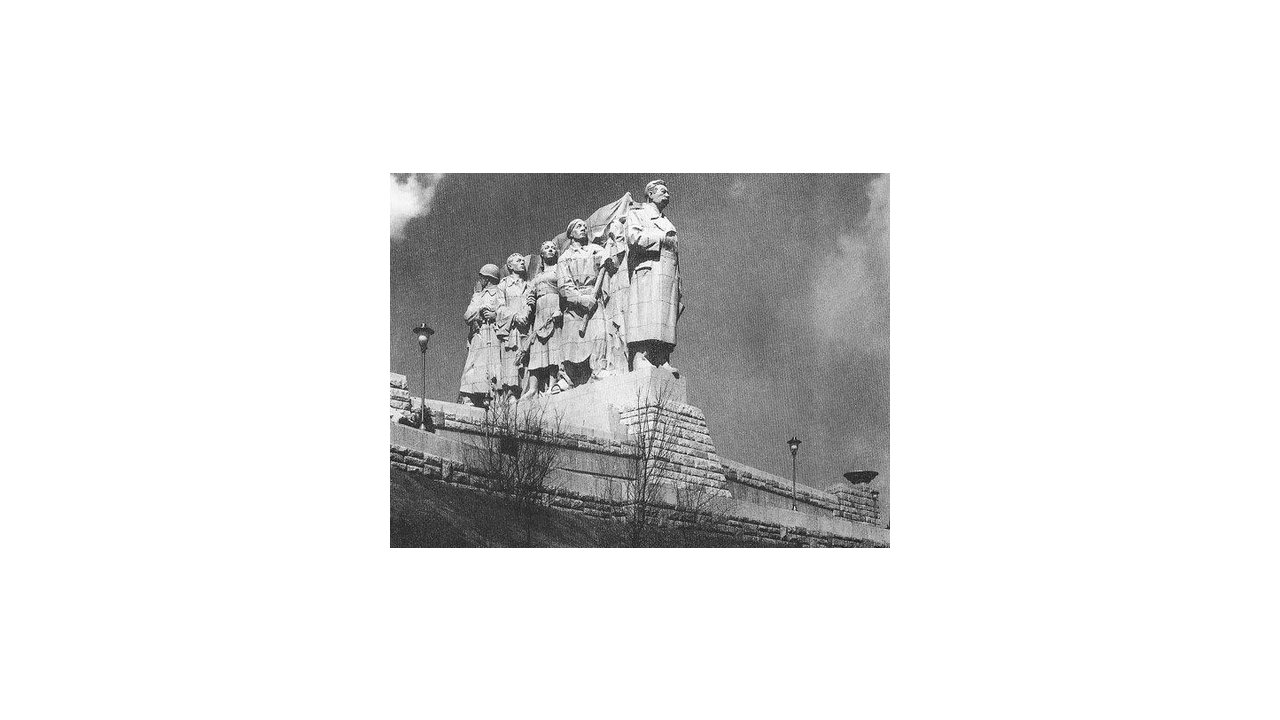

The favorite was actually Karel Pokorný, Czechoslovakia’s leading sculptor. “Pokorný probably lost because he showed Stalin with his arms outstretched,” Klimeš explained. Švec’s design had Stalin holding a book in one hand and the other hand on his heart. Behind stood socialist archetypes: a worker, a farmer, a female partisan, and a soldier. It was almost religious in its allegory. Perhaps this was why it was chosen.

According to a story recounted in Rudla Cailer’s slightly fictionalized Žulový Stalin (Granite Stalin), Švec got the design from his painter friend Adolf Zábranský. After a meal of goulash, Zábranský sketched Švec a design, and following some changes Švec accepted it.

Klimeš confirmed this account. “He drew the design on a napkin. Švec said that it was good. It would do.”

The Devil in the Details

Despite winning, Švec had to endure visits by an artistic commission, who made many adjustments. Only after this was done could construction begin in 1953, soon after the winter had thawed. The top of Letná Park was leveled and deep holes were sunk for the supports. The stones for the monument came from two quarries, one in Ruprechtice and the other in Rochlice na Libercku.

In the end, 7000 cubic meters of granite was used and 30,000 individual pieces carved. Klimeš explained that the stones had to be precisely cut in order to fit together. Existing photos from the time show the stonemasons chiseling away at the huge blocks, copying Švec’s model.

The monument took two years to complete. The pieces were transported to Prague, where a giant crane in the center would lower them in place. While the outside was made of granite, the inside was reinforced concrete. As Klimeš said, it was more like architecture than sculpture.

Klimeš was one of the large team of over 600 people who worked on the monument. Sculptors and stonemasons were teamed together, combining artistic and technical skills. Klimeš worked on the knee of the second man behind Stalin when the monument was viewed from the south side. He’s the one holding the wheat. That particular job took about six weeks.

Today, Klimeš works on a much smaller scale. His studio where we met is filled with his stone and bronze sculptors and plaster reliefs. The forms can be fluid, distorted or sensual. Not a single piece recalls the massive figure to which he contributed. Which begs the question: why did he do it?

“It was an adventure of the craft,” he said, though he didn’t see it as an honor to work on the monument and claims he wasn’t motivated by politics. He admits that he might seem like an opportunist. Why anyone would agree is difficult to judge from so long ago. Stalin’s cult of personality had a grip on all communist countries. Klimeš and the others who built the Stalin monument were among many who produced his image. However, the political climate was changing.

A Short Reign

The statue was unveiled on 1st May 1955. It was 15.5 meters high, 12 meters wide and 22 meters long and cost around 150 million in Czechoslovak Crowns. For the communists, it was an audacious show of loyalty to Moscow. Perhaps, Khrushchev’s absence at the opening ceremony should have been a signal.

The party’s efforts to immortalize Stalin’s image had no effect on the physical man. By this time, Stalin had been dead for two years. Even granite could not preserve his cult. Khrushchev made his so-called ‘secret speech’ in 1956, denouncing Stalin and the brutality of his rule. The monument and many other tributes to Stalin were an embarrassment, and had to go.

Changing a street’s name from Stalinova to Vinohradská was easy, but how were they going to get rid of a several thousand ton eyesore, which some people called it fronta na maso (the line for meat – a joke in reference to food shortages at the time)? For the communists, the answer was to do so with the strictest prohibition on any recording. No one was to photograph or film what had to be one of the largest acts of historical revisionism in history. It was to be as if the statue never existed.

But Klimeš didn’t heed the warnings. He took his camera to the demolition site, which was surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by police on all sides. He hid behind some nearby trees and documented the slow destruction from several hundred kilos of explosives used over a period of two months. The final piece was removed on November 6, 1962. Klimeš’s photos are some of the only visual records of the massive statue’s reduction to rubble.

Several stories have emerged about both the destruction and the aftermath. Stalin’s head was said to have fittingly fallen with the first blast, and fragments are alleged to have rained down on people on the other side of the Vltava. Klimeš dismissed the latter as hearsay. He also doubted that the story that the rubble was sold to England.

A Final Victim

The other story connected to the statue is the fate of its designer, Švec. He didn’t live to see the destruction. He didn’t even live for the unveiling. A month before the statue was unveiled, Švec took his own life. The reasons are disputed, as are the means. Rudolf Cainer claims it was from an overdose of sleeping pills.

And why? Was it because his wife died the year before? Was it, as Mariusz Szczygieł implies in his book Gottland, because a taxi driver pointed out that the woman was holding the soldier’s crotch? Was it pressure from the StB – the former secret police – who followed him? Was it the shame of being connected to the statue?

In a strange way, the regime didn’t even grant him that final reason. No mention of Švec was made on the monument.

Over the years, the area has served other purposes. A water filled statue of Michael Jackson stood there in 1996. Jan Kaplický’s prize winning design for a new National Library was mooted to stand there. Perhaps there’s something about the place, because sadly Kaplický passed away before the debate about his library was reconciled. Now the design is permanently on ice.

For now, the metronome keeps swinging, apart from the occasional power failure, counting the time until something else comes along to replace it.

Related articles

Reading time: 6 minutes

Reading time: 6 minutes