Behind Prague’s undeniably rich history are a wealth of legends and myths. These tales, sometimes magical and sometimes bloody, color the actual events. To some Czechs, these stories are an important part of their cultural identity. For the expat, they can be a fun read in their own right.

Libuše and the Foundation of Prague

Libuše was a legendary woman who ruled the Czech people back in the day. She had quite a unique ruling style, basing a lot of decisions on prophecies. For example, when she was pressured into marriage, she didn’t select any old prince. And she could hardly consult the personals. Instead, she insisted on marrying a man in her vision. He was a plough-man, named Přemysl, who would be found in the fields near the village Stadice. Now, that is picky.

Libuše’s servants approach Přemysl

Her decision to found Prague was based on the same mystical approach. Libuše had a vision a city “whose fame would reach to the stars.” She said the place would be near the river Vltava about 30 hons (4.5 kms) from where they were. Having trusted her method of selecting a husband, the people went to where she said and found a man making a threshold for a house. Threshold in Czech is práh, hence Praha. The site is what we know as Vyšehrad.

Maiden’s War

After Libuše’s death, the situation soured for women, so under the leadership of Vlasta, the dissatisfied ones left and set up a castle called Děvín (literally maiden’s) across the river from Vyšehrad, presumably to upset the men.

At first the men mocked the women’s attempts to learn swordplay, archery and horse-riding. That was all until Přemysl, who inherited both his wife’s position and leadership style, recounted a dream to the men as a warning. In the dream a young girl in full battle dress offered a goblet of blood for him to drink. The men thought the dream was nonsense and attacked Děvín. Přemysl’s prediction proved right and the women were victorious.

The Maiden’s War, with castle Děvín in the background

The outcome emboldened Vlasta. She planned to kidnap Ctirad, one of Přemysl’s most trusted men, while he was returning to Vyšehrad. As bait, she had a beautiful young woman, called Šárka, tied to a tree. Ctirad heard her pleas and freed her. Šárka offered him some potent mead, which she just happened to have. Once he was drunk enough, Šárka asked him to blow his hunter’s horn, thus alerting the maiden warriors. Ctiard, now presumably wiser about freeing strange women, was captured. The region Šárka is named for this deed.

Přemysl was so enraged by this deceit that he sent his men to attack Děvín. This time the women didn’t get the upper-hand and, well, let’s just say nothing remained of the castle after the attack.

The Naming of Smíchov

The suburb Smíchov apparently derives its name from the word smích, which means ‘laughter’, but the legend is not very cheerful. This story is set during the reign of Vojen, the third of the mythical Czech counts.

When Vojen came into power, he was too young to rule, so a Rohovic was appointed to govern in his stead. Rohovic was a stern ruler who punished any act, no matter how small. Eventually, the people decided they would prefer a young ruler than this guy. The upstart tried to stop the rightful ruler getting into the castle and escaped when they finally did.

Rohovic now turned to a life of crime, preying on the people in the Lucko region. Vojen sent a messenger to order Rohovic back, and Rohovic sent him the messenger’s head on a stake. Now things were serious. After 63 day seige of Rohovic’s stronghold, Vojen’s men captured Rohovic and brought him to Vyšehrad.

Vojen wasn’t in the mood for mercy and sentenced Rohovic to death on the river bank opposite the castle. While in the boat, Rohovic, who didn’t know when to quit, cursed and threatened Vojen.

Now, if you’re thinking that Rohovic, escaped and got the last laugh, hence the name, sorry you’re mistaken. The villain finally got his comeuppance. As for the laughter, it was due to the evil spirits which gathered around his body as he was executed.

Horymír, Šemík and the Great Escape

The reign of the fifth mythic count, Křesomysl, was a time of great prosperity because of silver-mining. Sadly, not as much time was spent on the fields and it is said that though people had lots of money they had no bread to buy.

Horymír was sent to warn the people. Instead of listening, the miners broke into his castle and torched what remained of his grain to punish him for being such a ninny and worrying about food. Horymír escaped on his trusty steed, Šemík, swearing revenge, which meant burning down the miners’ property.

The problem for Horymír was that the miners told Křesomysl, who sentenced him to death for his actions. Before the execution, he asked Křesomysl to grant a final wish. He wanted to ride his horse one last time. And these being simpler times, they let him.

Mounting Šemík, Horymír rode him up onto the battlements of Vyšehrad and down into the Vltava. As he leaped down the valley, Šemík allegedly turned to his master and said, “Hold on tight.” He then rode off to Neumětely and safety. People were so astounded they asked for Horymír to be pardoned.

Horymír escapes on Šemík

A messenger was sent to Neumětely with Křesomysl’s promise of clemency. Horymír returned, but this time without his faithful horse. The jump took its toll on Šemík and he passed away a couple of days after their escape. He is said to be buried in Neumětely.

Žito, the Court Magician

Now, we jump ahead to the time of Václav IV and the court magician Žito. One day, Žito turned thirty sheaves of straw into thirty large well-fed pigs, as you do when you’re a magician. A wealthy baker called Míchal bought the pigs, but Žito warned him never to let the pigs touch water. Míchal clearly thought this rule absurd. Pigs love mud. Mud contains water ergo he could safely take them across a stream, couldn’t he? No sooner had the pigs put their trotters in the water they turned into straw again.

The baker was so furious he went to look for Žito, finally finding the magician napping in a pub. He tried to wake the slumbering wizard by grabbing his leg. In his fury he tore it from Žito’s joint. Žito awoke and was now himself in a rage. He clutched the baker around the neck and together they went to the court, where the people could see the injury.

All the baker could do was beg for forgiveness and pay compensation, even though it was him who was sold faulty pigs. From this time, derives the saying “You have profited like Michael on his pigs,” meaning you haven’t benefited at all. A further moral could be that when dealing with people in government, which Žito belonged to at the time, it will always cost you.

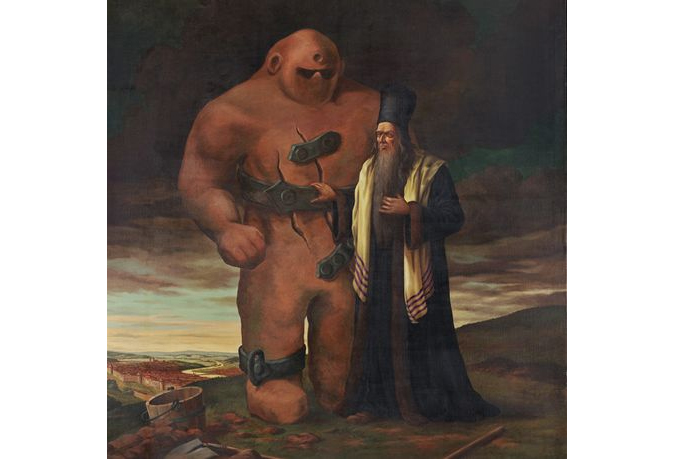

Rabbi Loew and the Golem

We’ve already mentioned briefly Rabbi Loew and his real historical contribution to Judaism. However, for many people his name is connected more with the legend of the golem.

Rabbi Loew and his Golem

The golem was made to serve the people of Jewish Quarter. Loew is said to have fashioned the creature from clay from the banks of the Vltava and brought it to life by inserting a capsule, known as a shem, which contained a scroll, in the golem’s mouth. Whoever inserted the shem had control over the golem.

Loew mainly had the golem do good works, helping the people in the community and protecting them from attacks. According to one version, the golem fell in love with a young woman called Sarah, and would follow her around like a puppy, albeit an immensely strong, gigantic, clay puppy.

On the sabbath, Lowe would remove the shem and the golem would remain motionless. One day, the Rabbi forgot, and without his master there, the golem became destructive, basically trashing the Rabbi’s home.

Loew returned and removed the shem and had the now lifeless golem placed in the attic of the New Old Synagogue, where it’s said it remained, slowing turning into a mound of dry dust. In another account, on the occasion of Loew’s one hundredth birthday, he went to see the golem. He was shocked to see that his creation was merely a head, and the head was crying. When the old man leaned down to wipe the tears away, he died.

Sources

The primary source of the legends is Alois Jirásek’s famous Ancient Bohemian Legends. Jirásek’s book is available in English in a number of editions, though most seem out of print.

Two other sources for these tales were Pověsti z Čech, Moravy a Slezska by Vladimír Hulpach and the recently published Prastaré Pověsti České by Petr Mašek. Neither are available in English at the moment.

These are just some of the legends of Prague. Not all of the many weird and wonderful tales could be included. Have you got any you’d like to share?

Related articles

Reading time: 7 minutes

Reading time: 7 minutes