WIN: To win tickets to see an English rehearsed-reading of the classic Czech comedy THE STAND-IN, click here.

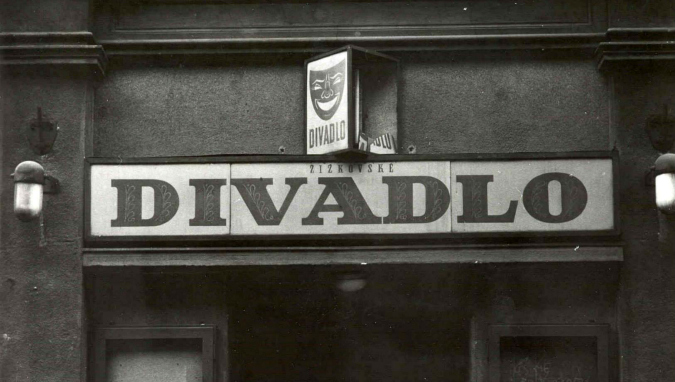

It’s generally said that to get Cimrman, the gifted polymath who never received his dues (but really the fictitious creation of Jiří Šebánek and Zdeněk Svěrák) you have to be Czech. While I don’t entirely agree with that opinion, you certainly need to speak the language because the plays and seminars, which usually precede them, have only been performed in Czech. That is until now.

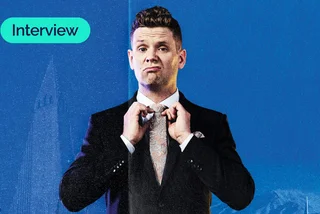

Brian Stewart and Emília Machalová have translated “Záskok”, (The Stand-In) in English, and there will be a public reading of the translation at Divadlo Járy Cimrmana on 20th June. A few tryouts have already taken place in the UK and the response was positive. “People were laughing and laughing in all the right places,” Stewart said.

Stewart, a British playwright, whose most famous work is “Killing Castro”, has been coming to the Czech Republic for a number of years. His interest in Czech culture spurred a desire to translate a work which would be indicative of this country. In part the desire was to go against the usual one-way cultural traffic: from the English-speaking world to the Czech Republic.

After seeing a Czech TV performance of “The Stand-In”, he had found his piece. “Although I don’t understand spoken Czech, I could see so much potential in there,” Stewart said. When asked to elaborate on the specific quality he saw, Stewart laughed like any Cimrman fan and said, “It’s just funny.”

The Stand-In concerns an amateur theater company’s production of its director’s own play, called “Vlasta”. “A big big mistake,” the main character, a prima donna called Karel Infeld Prácheňský, tells the director when he arrives as a last-minute stand-in.

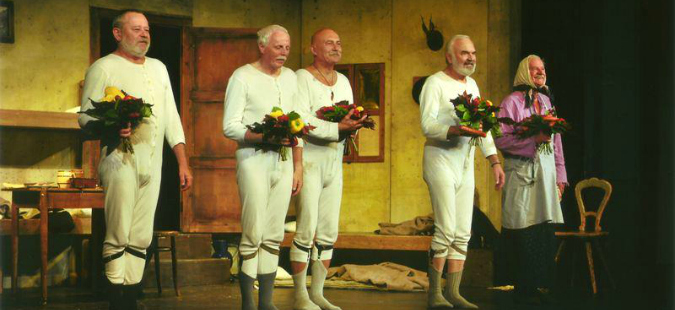

A play about a play may sound like intellectual deconstruction, but in fact it is artistic egos which get dismantled, hence the play’s broad appeal. At first Prácheňský, played by Zdeněk Svěrák and in the past by the late Ladislav Smoljak, has the cast of this small town ensemble in awe. Over the course of the play’s debut performance this egomaniac forgets his lines, says the wrong ones and tries to save the situation only to make it worse.

After finishing their translation, Stewart and Machalová consulted with Hanka Jelínková, the daughter of Svěrák. Stewart was honest about there being differences of opinion. Jelínková preferred a more literal translation where Stewart favored a looser approach if it worked better in English.

At the same time he and Machalová wanted to stay as true as possible to the play and keep the references to Czech history, which sometimes meant including explanations in the text.

“There was only one specific piece of the actual text we could not use and this was Mt. Říp and řepa.”

The particular joke is based on the fact that in colloquial Czech na Řípu (to be on Mt. Říp) and na řípu (to go to harvest beetroot) sound the same. The wordplay obviously does not work when translated.

Stewart acknowledges the trepidation of Czechs regarding bringing something uniquely Czech to a non-Czech audience. Yet he feels that people across the world share common situations. The translator’s task is to find a way to communicate that.

Lines from Cimrman

With Záskok getting the English treatment, we thought we would share some famous lines from it and other plays.

From Záskok (The Stand-in)

Prácheňský to the cast “Look, have you noticed which people sit where? So here in the center in the front row are the honorable guests. It’s clear. But here on the left it’s interesting, here the idiots always sit.”

Bárta, a character in the play “Vlasta” to the eponymous heroine…err hero. “You are not Machová. You are Mach?! You are not Vlasta? You are Vlasta?!”

Vyšetřování ztráty třídní knihy (Investigation of the missing class book)

Teacher to the class “Every joke loses its force with time. The class book goes missing, please. It is student fun and I have an appreciation for student fun. I also used to be a student. But, boys, we have been looking for this book already for the seventh year, and by now, don’t be upset, but by now it is slowly ceasing to be funny.”

Teacher to the headmaster “They are learning well, that I cannot say.”

The headmaster to the class “Sensible lads! These here are sensible lads? Let me tell you it is the but a moron or an idiot one beside the other. Moron, idiot, moron, idiot, moron, idiot, moron, idiot, moron, idiot. Right there at the back, it is maybe the one exception. There sits two idiots side by side.”

Hospůdka na mýtince

Innkeeper’s opening monologue “The postman came to me in the greatest urgency with good news: Your grandfather has died, you have become the owner of an inn in a forest clearing. And so I headed straight to the notary. The notary took an ax and food for three days and we set off. When, Ludvík my old – and it could be said yes, actually – only good friend, we cut our way to here, then I realized who my grandfather – may his soul rest in peace – was: an idiot.”

Dobytí severního pólu (Conquering of the North Pole)

[Explanation: Frištenský was selected for the expedition because he could pull the sled and cut wood.]

Expedition Chief: Men. Death by starvation threatens us. I have thought it over the whole night and I see no other way out. I suggest we eat the dogs.

(Meanwhile the others exchange confused looks.)

Teacher: Dogs?

Pharmacist: But we don’t have any dogs…ah, I get it.

(He glances at Frištenský, who is panting like a dog.)

Frištenský: (puts away his tongue and stops breathing loudly). What dogs?

Teacher: It’s sad when a person must lay a hand on his loyal friend, but really there is no other way out.

Pharmacist: Maybe it would be better not to eat everything at once, but to eat bit by bit. You know so that the remainder of the team would be able to pull.

Frištenský: What nonsense are you talking about? Maybe you are having hallucinations or what. Where do you see the dogs?

Expedition Chief: I don’t agree with that. When you put something down, so all at once. And soon. Before they lose weight.

**

Is Cimrman’s humor lost in translation?

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes