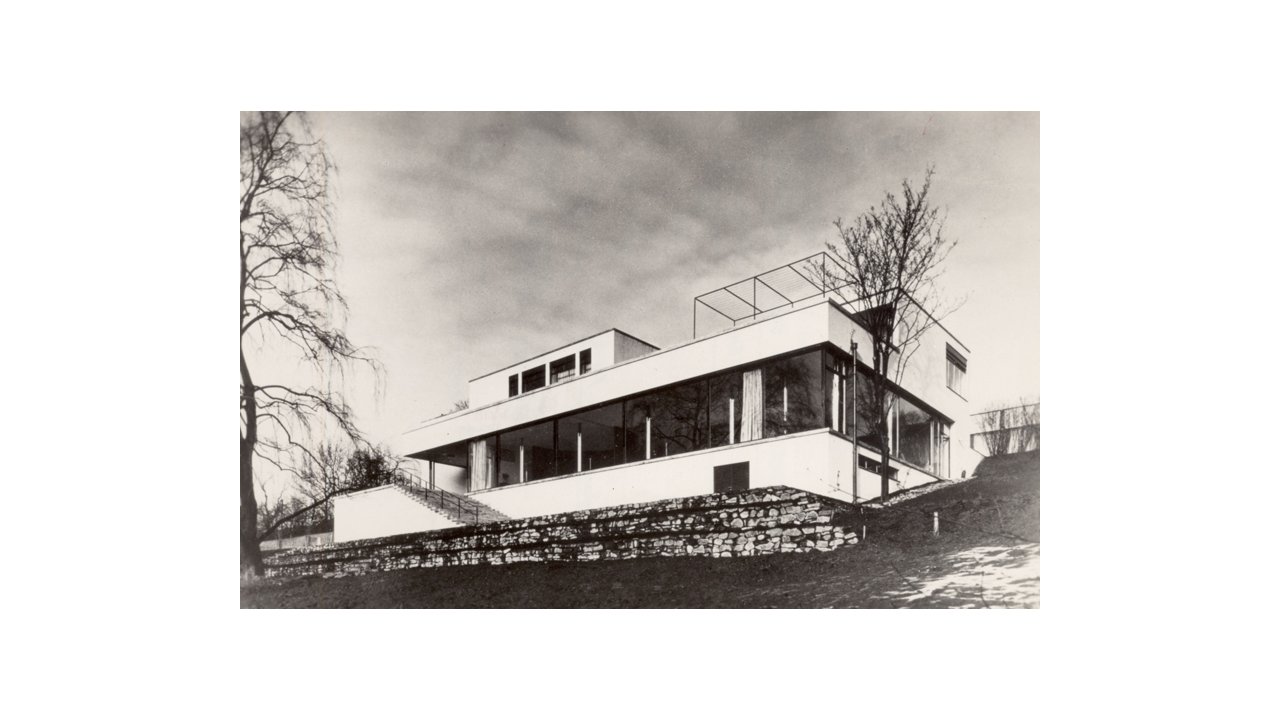

Located in Brno’s Černé pole neighborhood, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s ultramodern masterpiece has been many things: a family home, Gestapo headquarters, a dance school, a clinic, an inspiration for architects and the subject of a novel. Now, after almost two years of renovation and restoration, Villa Tugendhat is once again ready to welcome visitors through its doors.

Initial Conception

Architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was part of the European architectural avant-garde, which sought a break from traditional building styles. He especially wanted to simplify design. His famous dictum was “Less is more.”

Mies found a kindred spirit in Grete Tugendhat. The daughter of a Jewish industrialist family, the Löw-Beers, Grete wanted “a modern spacious house with clear and simple lines.” When she married Fritz Tugendhat, who was also Jewish, her father, Alfred, gave them the block of land on which the house now stands. The location is important because the view from the block was one of the reasons Mies accepted the commission. Grete’s father apparently didn’t approve of the initial designs, though he financed the construction, which began in 1928. The house was completed two years later and Grete and Fritz, along with Grete’s daughter from her first marriage, moved in.

Stylistic Considerations

The innovative and progressive design of the house is immediately apparent upon entry. It’s easy to forget that it was built in the late twenties because it feels like a building from a later decade. You enter at the top and descend into the large open living space. This inversion of traditional design is the least of Mies’ departures from conventional architecture.

His revolutionary approach started with the support. Twenty-nine steel columns hold up the house. This frame eliminates the need for load-bearing walls in the living area, so it is open, light, and spacious. The columns, still in their original stainless steel casings – now polished to a mirror shine, also form part of the interior decor.

Another break with earlier styles was an emphasis on the space itself over excessive ornamentation. The famous onyx wall, which divides the living space into a sitting area and a library, is the central feature. When the sun sets, the onyx catches the fading light and appears to flare up red in parts, a detail which Mies discovered by accident. The intricately-grained Makassar ebony used for the bookshelves and dining room partition is a further example of how the beauty of materials was favored over decorative art. (Though truth be told, the Tugendhats had a sculpture of a female torso in the living space and a painting of Alfred Löw-Beer in one of the bedrooms.)

Though the house was, mostly, unadorned, it still required furniture. Mies also contributed in this area, designing two pieces specifically for the home – the Tugendhat Armchair and the Brno Chair. The house also featured the Barcelona and Stuttgart Chairs, also the work of Mies. Designer Lilly Reich worked closely with Mies in the creation of the Brno and the Barcelona.

Technical Advances

Mies didn’t stop at the aesthetics of the space. He wanted the home to be comfortable. Among the most spectacular features are the two large (5m x 3.5m) windows which lower at the push of a button. The original mechanisms are still in use.

The Tugendhats’ comfort was further ensured by an air-conditioning system, again another first for a family home. The ventilation, which is unobtrusively incorporated into the walls, is controlled down in the cellar by a system of switches, allowing the occupants to control the temperature in different parts of the house.

An additional degree of comfort was ensured by the air filtration system. The air passed through a steel mesh, which constantly moved through a bath of oil, so to remove dust and pollen. The air then flowed through cedar wood chips to freshen it.

From Family Home to Icon

For all its technical and artistic marvels, the Villa Tugendhat was first a foremost a family house. Fritz and Grete enjoyed afternoon tea in the living room and games of bridge in the library. The children made full use of the large garden, which had ample room for sledding and skiing in winter. In the summer time, the family would get together with Grete’s parents, who lived in the adjacent villa below, to sunbathe and relax. The Tugendhats also hosted functions and parties, including bridge tournaments, the proceeds from which were used to help Jewish people fleeing persecution in Nazi Germany.

It was through these humanitarian activities that the Tugendhats became certain life for Jewish people would become more difficult in central Europe. After Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938, the Tugendhats predicted rightly that Nazi expansion would continue and so decided to abandon the home. Because they left early, they were able to take many of their possessions, including some of the furniture.

After the occupation in 1939, the Nazis used the abandoned house as a headquarters for the Gestapo. One of the major changes these new occupants made was to remove the rounded Makassar ebony panels, which partitioned off the dining area. The panels were only found later in the canteen of the Masaryk University Law School. Later, Wilhem Messrschmitt, the German aircraft designer, lived here.

Following the defeat of the Nazis and arrival of the Red Army, the house served as a barracks for a soviet cavalry division. The soldiers even kept their horses inside. From 1945 to 1950, it was a school for rhythmic gymnastics; then, when it became state property, an institute for treating children with spinal problems. It seemed that the new owners took the notion of functionalism a little too literally.

The building’s fate improved in 1969, when it was registered as a national historical landmark. Attempts from this time were made to restore it, but they were criticized for not maintaining the principles of the original. For example, the glass used was of a lower, less lustrous quality, and instead of using single panes, two panes were joined together for the large windows.

In 2001, the villa became a UNESCO cultural landmark, making restoration work a necessity.

Return to the Original State

The guiding principle behind the restoration was to return the house to the state when the Tugendhats lived there. To achieve this end, materials were used which were available at the time of construction. For example, the linoleum tiles on the floor and walls in the wet areas were made by the same formulas used by Deutsche Linoleum Werke, the company which produced the original tiles.

Painstaking care and attention was given to the plaster work. Again, the same plaster as was used in the house the first time was used in the restoration. The restorers even went so far as recreating the plastering styles of the different plasterers and maintaining the characteristic flaws in the original work.

Of course given the building’s history, quite a number of fixtures had to be replaced. The glass of the massive windows is not the original, but it was produced to be of top quality, so to be in line with Mies’ philosophy. The furniture also had to be replaced, though again the pieces retain the original design principles of the former items.

The restoration work was carried out under the auspices of the Tugendhat House International Committee (THICOM). The chair of THICOM is Ivo Hammer, husband of Daniela Tugendhat-Hammer, one of surviving daughters of Grete and Fritz. Mrs. Hammer-Tugendat was present at the opening along with her husband. So too was her older sister, Ruth Guggenherim-Tugendhatová. At the opening, Mrs. Guggenherim-Tugendhat said, “It must be clear to everyone, who looks around the villa, why our parents were so proud of the house.”

The total cost of the restoration came to 173.6 million CZK.

Visitor Information

The Villa Tugendhat is open for public visitors from March 6th. There are eight guided tours per day, each starting on the hour from 10:00. The last is at 17:00. It is necessary to book a tour using the villa’s booking system.

There are two tours to choose from: Standard, which is a tour of the main living area and bedrooms, and Technical, which is a tour of the bedrooms, living space, and air-conditoning and boiler room in the basement.

-> The Standard Tour is 300 CZK (180 CZK reduced). A family ticket (two adults and 1 or 2 children) for 690 CZK is also available.

-> The Technical Tour is 350 CZK (210 CZK reduced). The family ticket (two adults and 1 or 2 children) for this tour is 805 CZK.

-> Admission to the garden for an unlimited time is an additional 50 CZK per person.

The villa is found at Černopolní 45, Brno. The nearest tram stop is Dětská nemocnice, which can be reached by trams 3, 5, 7 and 11.

If you’re coming from the main train station, you can take trams, 4, 12 and 13, to the stop Česká, where you can take the trams 3, 5 or 7 to the villa. However, to make things interesting there are two pairs of stops called Česká, one on Česká Street outside the Constitutional Court (Ústavní soud) and the other around the corner on Joštova Street. Trams 12 and 13 will take you to the stop outside the court, where you can then catch the number 3 tram. Tram 4 will take you to the stop on Joštova where you can then catch trams 5 and 7.

If you intend to visit the restored villa, or saw it before, please let us know what you think.

Related articles

- 10 Travel Articles That’ll Get You Excited for Autumn In the Czech Republic

- VIDEO: Amazing Recreation of 14th-Century Construction of Charles Bridge

- Prague Is the Cheapest City In Europe for Ballet, Opera, Art

- Český Krumlov Mulls Over Charging Tourists a Toll

- New Travel Guide Puts Czech Monasteries On the Map

Reading time: 7 minutes

Reading time: 7 minutes