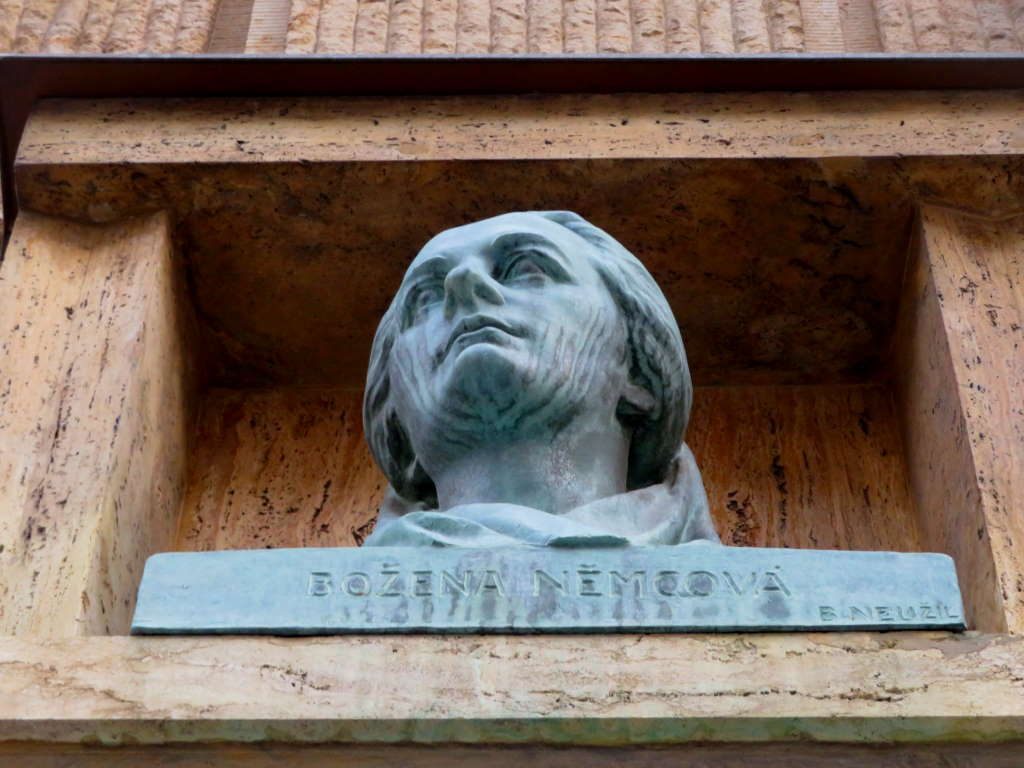

It has been 200 years since the birth of Božena Němcová, the Czech author of the classic novel Grandmother (Babička), whose face adorns the 500 CZK banknote.

She was a significant figure in the 19th century Czech revival movement, an opponent to the Austrian domination of Bohemia and a supporter of women’s rights

When she wrote Grandmother, as well as other works including fairy tales,few literary works were in the Czech language, as German was preferred.

She embraced the Czech language and causes when it wasn’t’ fashionable to do so. Vienna has instituted central control over its empire, an era known as Absolutism, which reduced freedom of the press and gave control over education and family life to the Catholic Church.

Němcová was born as Barbora Novotná on February 4, 1820, in Vienna, though there is some dispute over the exact date, with some experts putting it up to four years earlier. Her mother was Teresie Novotná, a maid.

Johann Pankel, a horse groomer, married Teresie Novotná after Barbora’s birth, and it is not clear if he is her actual father. He did give his name to the baby, though, who then became Barbora Pankel (or Panlová), She grew up in the North Bohemian village of Ratibořice, where where her parents worked in a manor house.Her maternal grandmother became a big influence on her life.

Her origin is a bit of mystery, leading some scholars to speculate that she was the unwanted offspring of a German noblewoman, and that she was given to a maid as a way of covering up the scandal, but there is no concrete evidence to back this up.

Her mother had little time for her children, and after the stint in Ratibořice she shipped Barbora off to a chateau Chvalkovice so she could improve her German language skills and manners. Her mother looked down in the Czech language and her Bohemian roots as being lower class.

When Barbora was 17 years old, her mother had no patience for her, and Barbora was married off to Josef Němec, a soldier and later customs official 15 years her senior. The hastily arrange marriage was not a good match. Němec was reportedly a strict disciplinarian, while Němcová, as she was now finally known, had an independent spirit. They had four children together.

Both were ardent supported of Czech independence. Němec dabbled a bit in journalism, writing some 60 known articles. But objected to his wife working as writer. He wanted her to follow the traditional role of a homemaker, and likely resented that she was far more successful than he was.

At least on one occasion, she sought protection from the police. On another she escaped out of a locked room via the window.

Němcová referred to marriage as a form of “privileged slavery,” and being forced to live a lie, while she preferred the truth. In Prague, she became a controversial figure, shocking some people with her atypical ways and opinions. She is rumored to have smoked cigars in salons, an activity at the time reserved for men. She also has a series of affairs with younger men from Prague’s literary circles.

Němec lost his position in 1853, due to his support of Czech causes, and fell into poverty. The couple then split up but did not divorce.

Němcová died on January 21, 1862 in Prague at age 41, in poverty and estranged from her husband. She is buried in Vyšehrad Cemetery, along with other significant Czechs.

Fellow author Václav Tille in the early 20th century praised the value of her work. “Němcová … created poetic prose from the living word. And Grandmother is a living word spoken at a time of deep silence in Czech literature,” he said. There are those, though, who criticize the floweriness of her written style.

Peter Demetz in his 1998 history book Prague in Black and Gold helps but her legacy in a more modern context. “Czech feminists are lucky that the modern Czech prose tradition begins in her writings. Instead of trying so hard to determine that her father was Metternich or another prince, it is far more important to grasp her pride and her thirst for independence, her plea for education (she had almost none), her defense of Jews … and her sudden decision to come in the disguise of a countrywoman to help the Prague insurrectionists of 1848,” he wrote.

He adds that since the Velvet Revolution, a new perspective on her work has started, with people looking into her letters and her more obscure works, and de-emphasizing the social realist interpretations from the previous era.

Reading time: 4 minutes

Reading time: 4 minutes