In less than a week my daughter is going on a camping trip. Not such a big deal in and of itself, unless you consider the fact that she’s 4 and neither I nor her dad or any immediate family or friends will be going with her.

For seven days she’ll relocate to the Moravian highlands, 100 km outside of Prague, with her entire preschool and a suitcase that’s twice as big as she is, filled with enough outerwear to suit up a small army. A small purple army. More on the two-page packing list later.

School in nature (Školka v přírodě or ŠVP) is a Czech tradition with German origins; the first outdoor school is said to have been established in 1904 at Berlin’s Charlottenburg Palace, located at the edge of an evergreen forest. The idea was to give city kids exposure to greenery and clean air.

The model spread throughout Europe in the 1920s, gaining popularity in France and Denmark. The concept is a predecessor of the modern “forest school,” where students are kept outside all day, exchanging desks and blackboards for meadows and blue skies.

In the Czech Republic, ŠVP debuted in the summer of 1924 when children with tuberculosis from Prague’s working-class Žižkov district were sent to learn and play in the countryside. By 1948 schools across Czechoslovakia regularly began offering their students the opportunity to attend these outdoor physical-education retreats.

While trips initially lasted as long as four weeks in the summer, by the early 1990s, ŠVP was shortened to a week, often taking place at different times throughout the school year.

Though the length of the trips may have changed throughout the years, the objective is the same: the promotion of a “strong body, strong mind for the greater good”, that’s somewhat in line with the ideology of the Sokol movement, designed to encourage personal growth and autonomy.

A fantastic concept, especially the part about fostering independence, but if you hail, as I do, from a country known to jail parents for sending their kids to the playground unaccompanied, the practice can feel unsettling, to say the least.

As an American mother of Czech kids I know I’m not alone in my fears. Many expat parents I’ve spoken to, including Leah Takata a Prague-based Canadian mom with two kids in Czech school, opted out of ŠVP for her preschoolers:

“I felt they were too young to go in preschool and so we waited until first grade. I was a bit nervous about health and safety…and [especially] with my oldest we decided to wait until he was a bit more focused and responsible,” Leah told me.

Leah’s decision is right in line with the advice I received from Dr. Désirée Gonzalo, a Spanish clinical psychologist with a practice in Prague, who says that it isn’t for nothing that kids start going to school around six years of age.

“It seems more reasonable to send children away on week-long trips once they have mastered a sense of autonomy, which can happen from around age 6, with variability,” she says.

Our oldest daughter attended ŠVP just before her sixth birthday. Despite an excessive amount of parental waffling over whether or not she should go and numerous crying jags (mine not hers) she made it through the week unscathed returning with news of pony rides, crafting sessions, and daily hikes.

But like Leah, I grappled with the idea of sending a 4-year-old who still ends up in our beds most nights to sleepover camp. My Czech husband, on the other hand, a proud alumnus of the ŠVP experiment, began an inventory of the family luggage right after the dates were announced by the school.

Dr. Gonzalo says tensions often arise when one’s partner approaches parenting based on the idea that “it was good for me” or “it is the tradition.” She says the deciding factor, aside from the child’s developmental readiness, should ultimately be: “Does your child have a good and trusting relationship with the adults going on the trip?”

It was this trust — bolstered by Annie’s determination to follow in her sister’s pony-riding footsteps — that ultimately led me to sign her up for school in nature.

The decision was also made easier by the reassurances of Annie’s principal Bc. Jitka Svátková, a veteran educator who has been leading kids into the forests and mountains of the Czech lands for thirty-plus years and who believes, like Dr. Gonazlo, that the success of the experience hinges on one factor: trust.

“Naturally, none of this would be possible if the families had no confidence in the school. Everything stands and falls on mutual trust,” says Ms. Svátková who told me that even Czech parents tend to freak out about ŠVP.

“I think today, especially with parents who are having children later in life, they can be much more timid and fretful.” To help keep everyone “calm,” Ms. Svátková, like a five-star general in the situation room, relies not only on daily e-mail and photo reports, but WhatsApp blasts and real-time Google travel dispatches.

She says despite their parents’ fears, the students she has worked with rarely experience serious separation anxiety.

“Children, if they are guided by parents to gradual self-determination and motivated to leave with the teacher, most of them, even [from a young age], can do it without problems.”

She also believes that this Czech tradition matters now more than ever especially in the age of the helicopter parent.

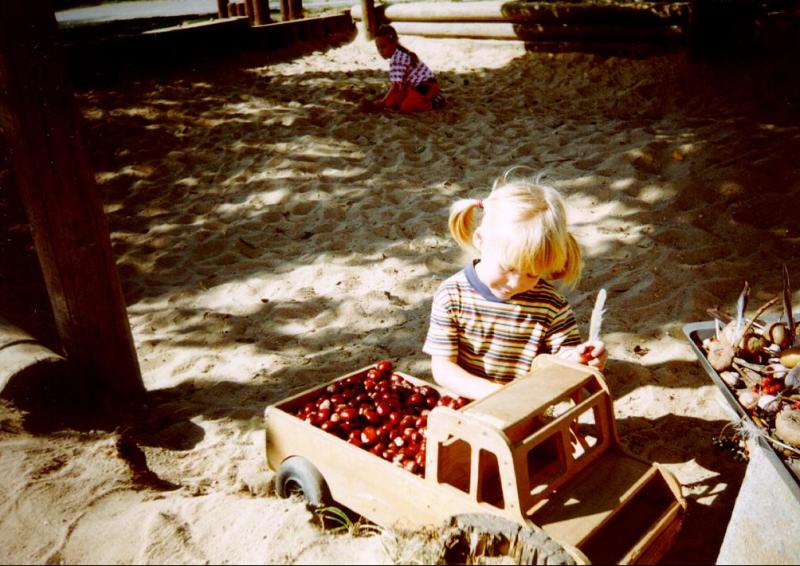

“Children learn how to problem solve, they also have a degree of autonomy without their family in the immediate vicinity. They experience a new way of doing things that’s different from what they are used to at home; taking care of their own things or communicating with adults. At the same time, their relationship with peers is strengthened by common experiences.”

For kids from cross-cultural families, the week-long trip can also be an education in the fundamentals of Czechness; my oldest enthused over eating the Czech foods that “mom never makes”, watching Večerníček at 6:45 on the dot every night, and spending hours outside playing and tracking animal footprints.

ŠVP is also a primer for expat parents in the Czech spirit of preparedness. Our packing list included no less than three different kinds of weather-proof pants, multiple sets of hats and scarves of varying thickness, and a carefully orchestrated list of personal hygiene products that included hand cream and lip balm to combat the pension’s hard water.

(Optional items: a shirt marinated in eau de maminka and as many toys that fit into whatever space remains.)

Svátková’s parting advice to parents who are still uncertain about letting their youngsters take part in school in nature:

“Believe in your children, motivate them to be independent, to know that while mom is always available for comforting them, they are smart and independent children who will soon be in school. ŠVP helps both the parents and children prepare for this.”

Sending Annie to school in nature (she’s now back safe and sound though looking decidedly taller) wasn’t a one-sided learning experience.

Though it may have been one of the scarier aspects of the culture I’ve personally confronted, it’s a Czech tradition that has given me a new parenting perspective — and a much-needed break.

Unless otherwise mentioned all photos courtesy of School in Nature Vřesník / vresnik.stampi.cz

Reading time: 6 minutes

Reading time: 6 minutes