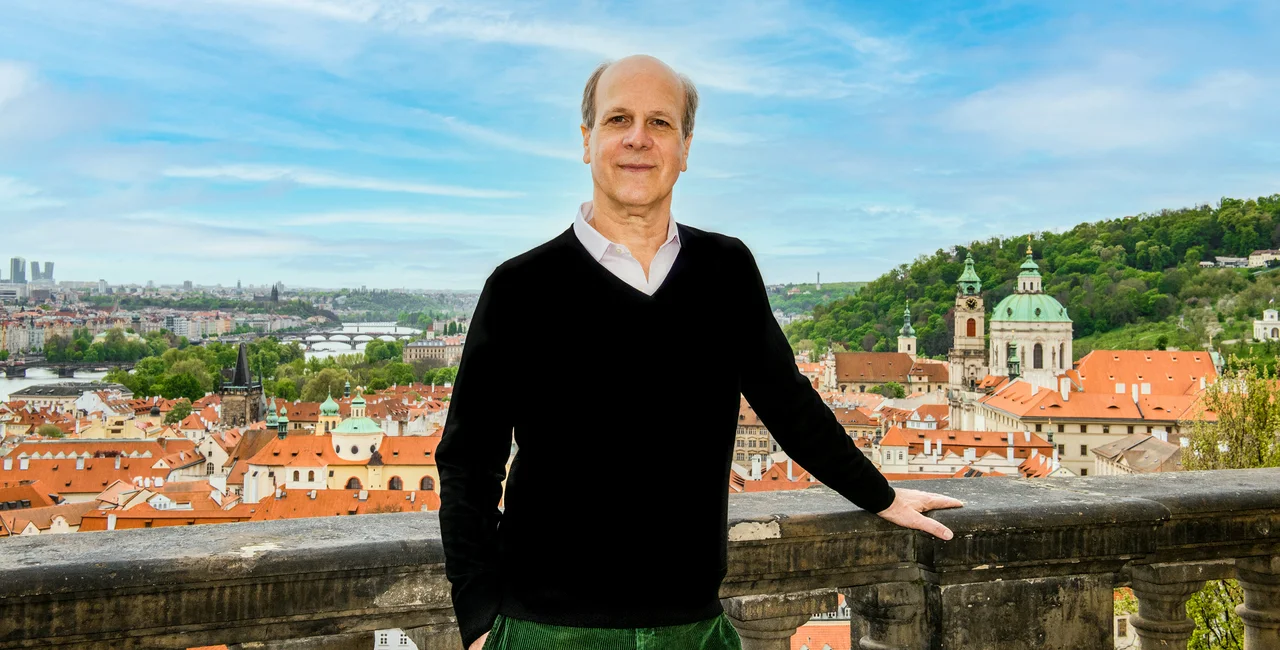

Meet William E. Lobkowicz for the first time, and you might not suspect that he belongs to a noble family that was, for centuries, among the most powerful in Bohemia. Brought up in the U.S. as an exile during the communist era, he exudes an affable American charm which, on first impression, seems a far cry from his family’s quintessentially Central European heritage.

Yet he is today one of the most significant figures in the cultural life of the Czech Republic. With its properties restituted after the fall of communism, the House of Lobkowicz operates Lobkowicz Palace at Prague Castle, the Renaissance-era Nelahozeves Castle, and the nearby Antonín Dvořák Birth House commemorating the famed Czech composer – opening this summer – as well as the magnificent Roudnice and Střekov Castles.

Expats.cz sat down with this Czech nobleman at Lobkowicz Palace to discuss the influence of his upbringing in the U.S., his family’s struggle to save its historic properties after communism, and the power of culture to heal societal divisions.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Do you ever feel like an “expat” in this country, having returned to Czechia from America during the 1990s?

Living in the U.S., we knew our history very well and knew that we had been a core Bohemian family for 700 years. We knew relatives who were refugees; my dad helped them, and our house was always filled with stories of the old country, which fascinated me from a young age.

I didn’t predict a revolution, but I always had a feeling that one day, things would change, and we would come back. Yet when I returned, I knew I hadn’t grown up with the same experiences as people here. I felt very fortunate but also a little guilty. I don’t think any of us can fully understand what it was like to live for so long under communism.

We were strongly influenced by former Czech President Václav Havel, the first leader from Central and Eastern Europe to come to the U.S. and speak to a joint session of Congress. This left a big impression on me. Havel’s brother came later that year to a lunch hosted by my father and told us: “It’s time to come home.” I’ll never forget that moment. Within six months, I had moved here permanently.

I like to think that we bring some “American” ways of thinking that might be helpful here; that’s how I see the expat part of me contributing to Czech society.

Did you always plan to open your properties to the public once you regained ownership?

Yes, for a couple of reasons. Our property was vast, and after 50 years of destruction, around USD 50-100 million (around CZK 1.2 billion to CZK 2.4 billion) of damage had been done, including untold environmental damage to forestry and land, which could have produced income.

We decided that if we could get these properties back, that would be the way to open them to the public. In the end, it took us nearly 27 years to reconstruct our family ownership; the process only finished in 2017, and it’s the reason I have no hair left!

We felt very fortunate to be able to come home, and we wanted to contribute. At that time, we were a well-educated, typical upper-middle-class U.S. family. We understood that if you want to achieve something, you have to work hard for it.

As a family, we didn’t have the resources to repair these properties ourselves. We liked the English model, in which country houses are turned into schools, museums, conference centers, and beautiful gardens supported by cultural heritage organizations.

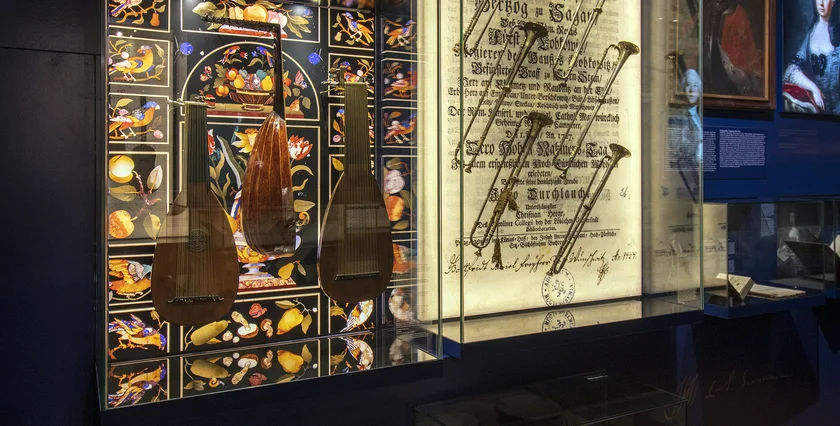

We started by raising money in the U.S. to take care of our collections, including movable objects, which are national cultural monuments. This is a very “American” approach. In the U.S., there’s no Culture Ministry; people set up non-profit organizations, contribute, and get a tax write-off, allowing culture lovers to fundraise for their community. At the same time, we created a for-profit events management business, thanks to which we were able to start repairing our properties.

We’ve done our job well if people are interested in coming here and are willing to buy a ticket or if they decide to hold their wedding or corporate event here. By doing so, they are contributing to the upkeep of these special buildings.

It’s a never-ending job, and we’ve had terrible problems along the way. It took us five years to recover in terms of visitors after 9/11, then there was the 2007-2008 financial crisis, and then Covid-19 arrived; we were locked down with just four people allowed in this building. Last year, we just barely reached where we were in 2019.

You are keen on Prague Castle becoming more accessible to the general public; what would this look like to you?

Prague Castle is the pride and joy of the country, so it should always be accessible. It’s never been closed, but it hasn’t been as welcoming as it could be, especially to Czechs.

The new administration has said – much to my delight – that they want to make the castle more open. Finding the balance between tourism and local appeal is key. After all, there will always be a lot of foreign tourists here, as it’s an important source of revenue for the tourism industry as a whole.

I think the opportunity lies in programming and special events. An event was held here for the 30th anniversary of the Czech Republic, during which the crown jewels were on display while we displayed the Order of the Golden Fleece, the highest order of chivalry. It was such a fun four days; people came from all over the country, and seeing how proud everybody was made a big impression on me.

Some festivals, such as Open House and Signal Festival, as well as literature events and other activities, can bring people here. We can also find creative opportunities with the church, which wouldn’t need to be religious.

Why do you think it’s particularly important for locals to enjoy visiting the castle?

We live in a very fractured world in which people tend to only listen to the ideas of their own camp. We need to build more bridges, and we have a tremendous opportunity to do this through culture and heritage, which this country is so rich in.

By creating a wonderful concert or a festival where everyone can sit outside, drink delicious Czech beer, and think about their shared history, we can build a stronger community. Culture is at the bottom of everyone’s list and the first thing that’s cut in a crisis – but we all need it.

Can you describe the goal of the Dvořák Birth House renovation currently underway in Nelahozeves?

We got the Dvořák’s Birth House back in 1993 and leased it to the National Museum for a symbolic CZK 1. In 2019, we were finally ready to take it over, having made a master plan of development for Nelahozeves in 2016. We took it on – and then, six months later, Covid-19 hit! The project we thought would take two and a half years is now in its fifth year, but it’ll finally open this summer.

We have turned it into a “house of inspiration.” When you arrive, you should ask the question: How did a poor butcher’s son in the 1840s become the colossus that he remains to this day? It’s a story about how anybody can become anything they want to be.

We explore Dvořák’s inspirations: the riverboats, the trains (he wanted to be a train conductor if he wasn’t successful as a musician), the church across the street, where the cantor taught him to play the violin, the house that he lived in, where his father played the zither, running a little tavern with a dancehall on the other side. It was the core and heart of the village.

We’ve reoriented the building so that you enter from the town square, allowing people to be outside in nature, which was another of Dvořák’s big inspirations. Behind the house, we’ve built a meditation garden for music therapy activities, with a beautiful view; this will be a great space for musical events, cocktail parties, yoga sessions, and educational activities. In the old horse stables, we’ve created an educational space and been allowed to rebuild the barn that burned down during Dvořák’s lifetime.

The mayor and the town, as a whole, have been amazing. They’ve fixed the train station so that it’s back the way it was in the 1800s while the church is being renovated. We’re doing all this in coordination. We’ve also taken over a marina just below the castle, with accommodation and wonderful outdoor spaces.

Is the broader development of Nelahozeves an example of the positive change that culture can instigate?

The whole town is experiencing a renaissance, and the core of it is the Dvořák Birth House, as well as the 100-room Nelahozeves Castle, which we’re reviving with new exhibitions and activities. Visiting Nelahozeves will be an exploratory, historical journey.

It isn’t all about Dvořák – there’s nature and the castle, too – but music is such a great connection. My ancestors weren’t patrons of Dvořák in the way we were with Beethoven, for example, but we have this wonderful opportunity, through his house, to create something unique.

Is this project particularly close to your heart because you are a musician?

I’ve been an amateur singer going way back. Before I came to the Czech Republic, I was a real estate broker in Boston, and in my free time, I tried to build a repertoire to become an opera singer. Anyone willing to sit in a room and listen would hear me sing Fauré, Brahms, Schubert, Vaughan Williams, and so on. I still sing a little; I sang for my kids when they were baptized and for my wife’s birthday last September.

Music runs in my family; we’ve put on 5,000 concerts over the past 35 years, with a concert every day of the year. It’s wonderful that we can be even more involved in music through the Dvořák Birth House; I think this was my destiny.

There’s a song I particularly love – "Goin’ Home," a section of the Largo from Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 – which is very poignant for me because it was created by an American who studied with Dvořák while he lived in New York. Dvořák was the head of the National Conservatory of Music of America, and he composed Symphony No. 9 based on the inspirations all around him.

In 2021, the great cellist Yo-Yo Ma visited the Dvořák Birth House for the first time. I was due to sing “Goin’ Home” at a Dvořák festival a few days later, and Yo-Yo made me sing it to him. He then insisted on holding an impromptu masterclass with young students under the statue of Dvořák at the house; I’ve never seen a group of people so excited in my life!

These special moments continually remind me of the power of culture. It’s our core identity; it’s what we have inside us. We have to harness this power to bring people together.

Reading time: 9 minutes

Reading time: 9 minutes