Czechoslovakia almost had a space program. One scientist and entrepreneur envisioned rockets not only going to space but also delivering mail from Europe to the Americas.

On March 2, 1930, Ludvík Očenášek launched eight solid-fuel rockets from Bilá hora, with one reaching a height of two and a half kilometers. Another rocket more symbolically exploded on the ground.

A real-life Jára Cimrman

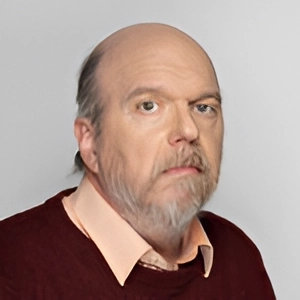

Očenášek is all but forgotten today, but throughout his career, he made numerous inventions in aviation engines, a parachute, electric arc lighting, anti-aircraft and anti-tank weaponry, a silent machine gun, audio speakers, a new type of unicycle, and machines to count pills. But success eluded him, as other inventors were better at patenting and marketing.

Czech news sites Aktulane.cz and Seznam Zprávy called him the real-life Jara Cimrman, referring to a fictitious and similarly luckless inventor made famous in satirical plays and radio shows.

What Očenášek is most remembered for now is tapping into phone lines between the ministries of defense in Vienna and Berlin during World War I. His listening station was in Prague 5 in the garden of what is now the Lithuanian Embassy, which has a commemorative plaque on the outside wall.

He passed the information to Czechoslovak resistance groups working under Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. He also fought against the Nazis in the Prague Uprising in the last days of World War II, helping to defend the Czechoslovak Radio building at the age of 73.

He began experimenting in rocketry in the 1920s, which made him a true pioneer in the field, working at the same time as Robert Goddard in the U.S. and other inventors in Germany and the Soviet Union – though his name is seldom included with his peers.

Transylvanian scientist Hermann Oberth and Swiss inventor August Piccard both came to Prague to see his work firsthand, and were not disappointed.

A moon launch hoax set him up for ridicule

While his rocket experiment in 1930 should have been hailed as a success, it was instead seen as anticlimactic. The newspaper Berliner Morgenpost ran a joke article on Christmas 1929 saying Očenášek was planning to send a spaceship to the moon.

“Two passengers have already signed up to take off into outer space, which is being prepared by Prague engineer Ludvík Očenášek: a university student from Prague and Mr. Max Deutch from Olomouc. The rocket will be launched in spring at moonrise. Engineer Očenášek calculates that the flight will last 87 hours. The rocket will have six propulsion rockets and two braking ones. Nine people can take part in the trip, but only Czechoslovak nationals,” Berliner Morgenpost reported.

The faux story was picked up as fact by papers across Europe. Očenášek received hundreds of letters from as far away as the United States from volunteers wanting to make the lunar voyage.

A 1968 report on space travel by the Smithsonian quoted one of the letters from 20-year-old Sally Gallant of New Castle, Pennsylvania. She listed her qualifications as speaking Polish and English, being a nurse, and having blonde hair. She also included her height and weight. Apparently, a Polish newspaper she somehow acquired had a copy of the false story.

The rather small rockets launched in 1930 were not what the public had been falsely led to expect, and due to the economic downturn in the 1930s, no follow-up launches took place.

Očenášek’s various but scattered attempts at inventions landed him in financial trouble and he ended up in bankruptcy, as no local investors shared his vision of delivering mail via intercontinental cargo missiles.

Oddly, he was not alone in his mail-by-rocket idea. Similar experiments led by a German rocketeer took place in England in 1934, and in the U.S. on June 8, 1959, some 3,000 letters were sent by "missile mail." The special envelopes from the latter are sought after by collectors.

While Očenášek’s Bilá hora rockets used sold fuel similar to gunpowder, he was already planning larger rockets with liquid fuel such as hydrogen and oxygen, similar to what the space programs of the 1950s and 1960s eventually would use.

The New York tabloid The Sun in an April 1930 article titled "Mail by Rocket Is Latest Plan; Czech Inventor Working on Device to Cross Ocean; Confident He Will Succeed" quoted Očenášek on the future of space travel. He was surprisingly accurate:

“Indeed, rockets with human crews are not improbable, although in this case, many difficult problems concerning the physiological reactions of the human body will arise,” he told The Sun.

While there are photos and even some film of the 1930 rocket launch, many of the technical details are not known. Only a part of one of his rockets survived until 1968 when the Smithsonian reported on it.

Experiments leading up to World War II

His research wasn’t a total loss, though. He adapted his rocket engines to power boats in shallow waters, with financial support and encouragement from the Baťa Shoe Company, which wanted to deliver its footwear via what the Smithsonian called “the shallow unregulated rivers of central Europe.”

His boats showed some promise, though they never were perfected enough to deliver shoes. The Czechoslovak military tested several prototypes, and other countries wanted the technology. The occupation of Bohemia just before World War II put an end to this research.

One of the most mysterious parts of Očenášek’s career was a return to rocket research for the Czechoslovak government just before World War II. All that remains is a single photo of what looks like what we would now call rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs).

He apparently hoped to share the designs with Czechoslovakia’s allies fighting against the Nazis but was not successful. The Nazis attempted to have him help them in developing their rockets, but he refused. He knew he was under close surveillance, and this limited his chances to help the resistance with any of his plans

Written out of history

He died in 1949 at the age of 77 and is buried in Olšany Cemeteries. His tomb seems to have been vandalized or simply let to fall apart from decay at some point, as the current stone does not match a photo from 1968. The new stone does not even list his dates of birth and death, or hint at his career.

His name is not listed on the map of famous cemetery occupants, and there is no tourist information sign next to it, as other famous and even obscure people have.

His life story as a factory owner, lifelong member of the patriotic Sokol movement, and supporter of democratic ideals did not fit in with the agenda of the communist regime in the 1950s. He was left out of Czechoslovak history books, which favored accounts of Soviet scientists when it came to anything space related.

The Prague 5 district in cooperation with the Lithuanian Embassy in 2022, on the 150th anniversary of his birth, began an effort to revive his legacy by temporarily placing some info panels in a square and issuing comic books about his life for schools. Since 2005, an asteroid in the belt between Mars and Jupiter has been named after him.

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes