The word of the year, at least for Prague and major cities in Europe, is “overtourism.” A combination of discount flights, shared-accommodation apps and online must-see lists has led the main sights to be so crowded that it is virtually impossible to see anything.

But places just slightly off the beaten track have very few tourists and often lots to see and do. Top on the list of unjustly ignored places to bring visiting friends, or just go and see by yourself in peace, is Vyšehrad, the higher castle. It is easily reachable from the C-line metro station of the same name.

The high brick walls from when Vyšehrad was a fortified military post now provide lovely photo vantage points looking at bridges across the Vltava river with Prague Castle in the background.

There are several green fields for relaxing and numerous eateries offering everything from ice cream and chips to sit-down meals, at prices lower than in the more touristed center. The spaces are open enough that it is easy to sit with friends for a picnic.

The popular Hospůdka Na Hradbách, located along the defensive walls behind the Leopold Gate, has an outdoor beer garden with Balkan food on the grill. A little more upscale is Cafe Citadela, located next to a small vineyard closer to the Vltava. Small snack bars also dot the area.

The history of Vyšehrad dates back to the 10th century, when it was the seat of Přemyslid dynasty. Near the small vineyard, next to an art gallery, are the outlines of two buildings from that time. A Gothic cellar with a historical display is in the same area.

A legend says that Princess Libuše, the founder of the dynasty, stood on the rocky outcrop of Vyšehrad and looked toward where Prague Castle now stands, seeing the future of the Czech nation. She was the subject of the first opera ever performed at the National Theatre.

On the stone cliff leading down toward the river are some evocative ruins called Libuše’s Bath, but actually they are much more recent.

Back by the Leopold Gate stands one of Prague’s oldest standing buildings: the 11th century Rotunda of St Martin, a small church shaped like a vertical tube. Near the rotunda is a plague column from the 17th century, built to mark the passing of an epidemic.

Heading down this path, past a small chapel. eventually takes you to the Brick Gate. From April to October you can get inside the fortress’ walls from 9:30 am to 5 pm. (From November to March the last tour is at 4 pm.)

At the end of the walk inside there is a surprise: some of the original sandstone statues from Charles Bridge in a large space called the Gorlice. Most of the statues on Charles Bridge are now copies.

When you exit the Gorlice, you can head toward the large Basilica of Sts Peter and Paul, unmissable due to its huge spires. But before you get there, you will pass an odd stone column broken into three pieces.

This is called the Devil’s Column, and there is a tale that a demon named Zardan threw the pieces in the ground after losing a bet with a local priest. A mural in the basilica depicts the legend.

To the left, as you face the church is a small snack bar with a mysterious door next to it. The door leads to the foundation of the 11th century Basilica of St Lawrence.

Keys to get in can be borrowed from the Parish Office at K Rotundě 100/10 from 10 am to 3 pm. Instructions, in Czech with a little English, are on the site’s door, and the office can me reached in advance by email at info@kkvys.cz.

The field to the left side of the church has four very large statues. These depict four pairs of legendary figures, including Princess Libuše and her husband, Přemysl. They originally stood at the Palacký Bridge and were moved during World War II.

These were sculpted by Josef Václav Myslbek at the end of the 19th century. He is best-known for the Saint Wenceslas Statue on Wenceslas Square.

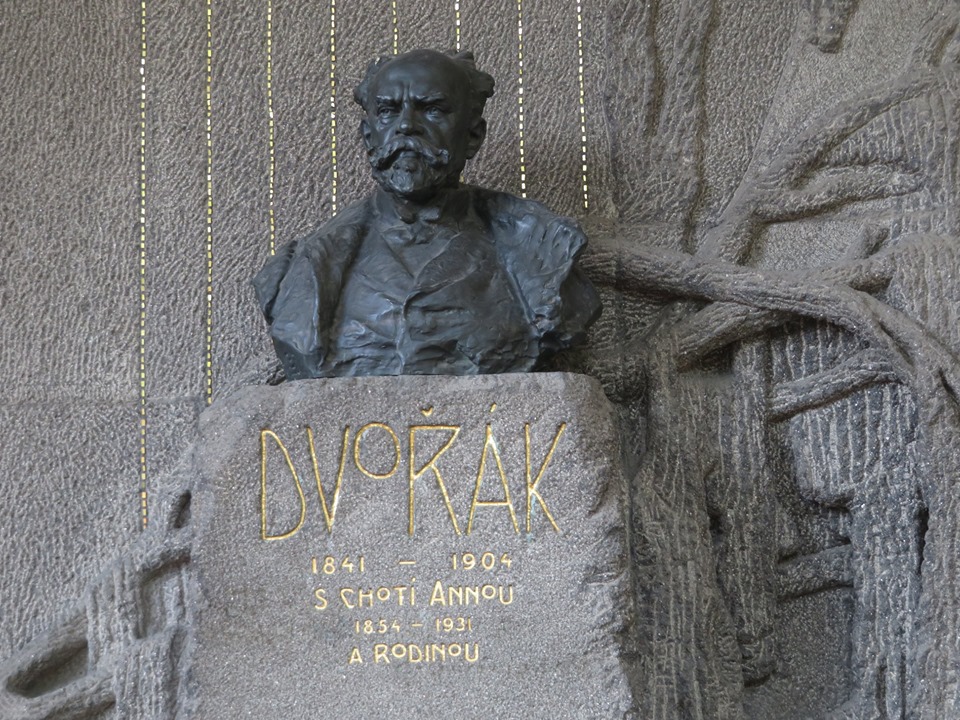

Around two sides of the Basilica of Sts. Peter and Paul is Vyšehrad Cemetery, with the ornate graves of many famous Czechs such as composers Antonín Dvořák and Bedřich Smetana, writers Karel and Josef Čapek, poets Jan Neruda and Karel Hynek Mácha, and many others.

The neo-Gothic Basilica of Sts Peter and Paul itself was built between 1887 and 1903, making it relatively modern compared to other Prague churches.

Still, the church has some items of interest. In one of the niches near main the entrance in a glass and gold case is a shoulder bone allegedly from St Valentine, the person remembered on Valentine’s Day.

Also near the entrance but on the other side is the stone coffin of St Longinus, who according to Christian tradition was present at the Crucifixion. The lid and bones were lost hundreds of years ago, perhaps during the Hussite Wars.

A third notable item is a 14th century painting called the Vyšehrad Madonna, or the Madonna of the Rain. The church now displays a copy. The original is held by the National Gallery.

A long-standing tradition is that burning a candle in front of the painting will ensure a healthy baby, and young women can still often be seen praying by the painting.

There is also a treasury room with religious clothing, chalices and other valuable objects.

Outside, beyond the cemetery walls is another field with a stone statue of St Wenceslas, by sculptor Jan Jiří Bendl. This version, made in the 17th century, was part of a fountain at Wenceslas Square until 1879, when it was moved to make room for the square’s current statue.

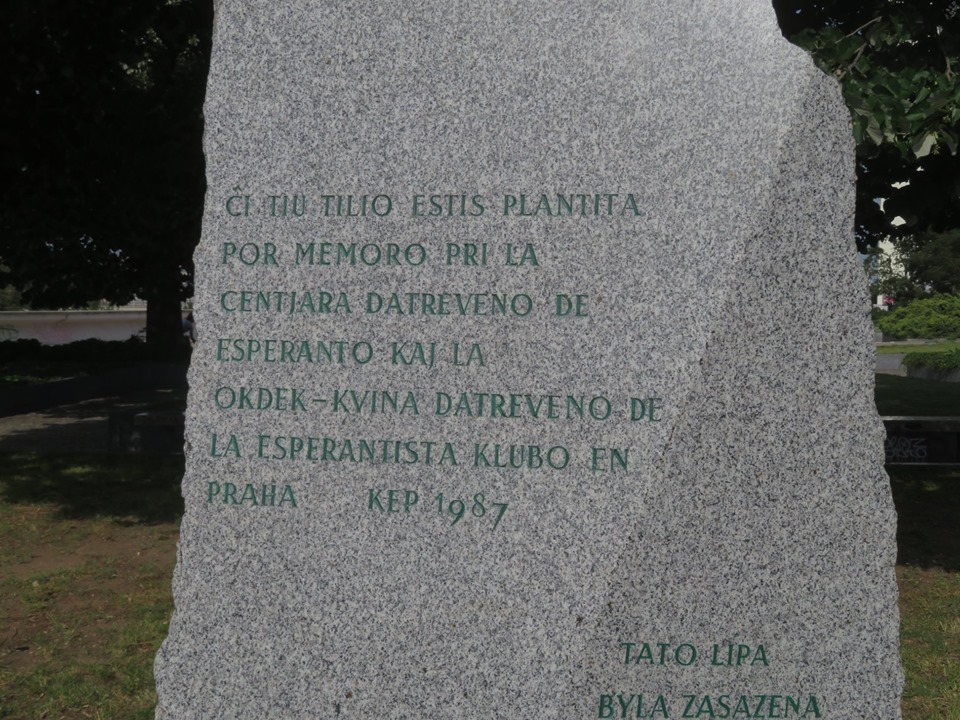

There are also some things to see outside the fortress. If you come from the Vyšehrad metro stop on the C line, there is a tree planted in 1987 to promote the artificial language Esperanto, with a stone that has an inscription in that language.

There is also a sculpture with a glass pyramid on a metal base called Pyramid 04, by modern artist Marián Karel.

Heading a little closer to Vyšehrad, hidden in a parking lot behind the Holiday Inn, is a communist-era bronze sculpture of a mother and daughter in rather sheer outfits. It comes from the era of Normalization, when every public construction project had to include a piece of art.

Going down from Vyšehrad by the hard-to-find steps behind the wall just opposite the entrance to Basilica of Sts Peter and Paul, you will encounter some of Prague’s Cubist houses. Three are together on the waterfront on Rašínovo nábřeží 42/6, 47/8 and 71/10. Another is at Libušina 49/3.

Exiting from the Brick Gate, you will find two more Cubist buildings on Neklanova 98/30 and Neklanova 56/2. All of them are the work of architect Josef Chochol except for Neklanova 56/2, which is by Antonín Belada. They were built between 1912 and ’14.

A bit far from the fortress’s exits but still part of the greater Vyšehrad neighborhood is the Vyšehrad-Praha train station (Nádraží Praha-Vyšehrad) at Svobodova 86/2. The abandoned Art Nouveau building, built in 1872 and closed in 1960, is in very poor technical condition.

It has been listed as cultural heritage since 2001, and was sold to private company in 2007, but never reopened.

Prague 2 has been seeking to find a use for the building and a new investor to take it over. Earlier this year, Prague 2 suggested the building be renovated into an art gallery that could display the Slav Epic, a series of 20 large paintings made by Alfons Mucha between 1910 and ’28. This seems unlikely, though.

Events and exhibitions being held at Vyšehrad are listed on the Czech page of http://www.praha-vysehrad.cz/.

Reading time: 6 minutes

Reading time: 6 minutes