Many of us take the Prague Metro every day. We hop on and hop off, without realizing the stories the Metro hides. Some aspects have been deliberately covered following the transition to democracy. Other details are located deep down in the tunnels. In the first of a two-part series, we look at the Metro’s other, more closely guarded, purpose.

Underground Defense

When you’re at Dejvická Station, turn and look down the tunnel in the direction back toward the city center. Just within the transit tunnel’s mouth (passed where the interior of the station proper ends) you’ll notice a large heavy square door, held open against the outer side of the tunnel. That door is one of several throughout the Prague Metro System. In the event of an attack on the city, they should close to turn the designated stations into hermetically sealed bunkers. The doors can allegedly withstand a nuclear blast on the surface as well as a “torrential” wave of water. Up to 300,000 people can allegedly take refuge in the system for three days.

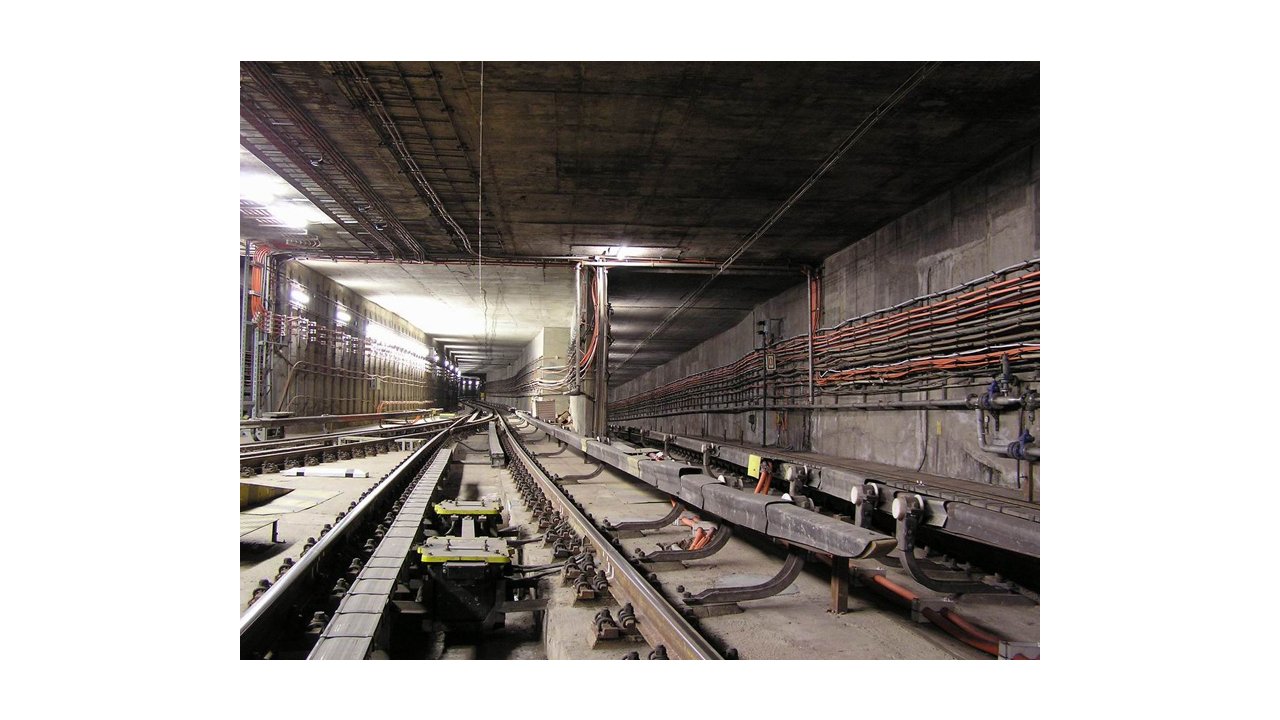

The bunkers form part of what is known as Ochranný Systém Metra (Metro protection system), or OSM for short. Only the deepest tunnels, which had been drilled into the earth, were appropriate for the purpose of housing people during war, because they were far enough away from the surface to be properly sealed. These stations, known as ražené stanice, are characterized by the circular nature of the walls at the station. Think Staroměstská station and you have an idea.

The OSM includes Line A (Green) from Dejvická to Želivského and Line B (Yellow) from Nové Butovice to Českomoravská. The stations which are not part of the system are those too close to the surface. These so-called cut-and-cover stations (hloubené stanice) have the straight sides. While Nové Butovice and Dejvická are both cut-and-cover and have the blast proof doors, the stations themselves do not form part of the bunker system.

Officially, there’s not much information on the OSM. The website for aficionados of the Metro, Metroweb, is perhaps the best source of information. It’s the one place where you’ll find many pictures. On the linked page (in Czech) it’s claimed that the system includes “underground hospitals” (really spaces for treating the sick and injured), food stores, washing facilities, toilets, and a mortuary.

Though the OSM is no longer classified – in fact, it’s something of an open secret – coming by other information is not so easy. The Prague Public Transit Company (Dopravní podnik hlavního města Prahy, or DPP) declined a request to visit one of the control centers. The main person who was willing to talk was the head of the DPP archive, Pavel Fojtík.

One question which Mr. Fojtik has heard often is why the OSM was not used against the floods in 2002. For him, there were a couple of reasons.

“Firstly it happened relatively quickly. Secondly, no one was counting on what happened to happen,” he said. To these points, there is the technical matter that the system was not designed as anti-flood system. Furthermore, OSM takes a couple to several hours to be prepared. It’s not a matter of someone pressing a button.

“As far as I know it works. Relatively recently they carried out a test whether it can be closed or not because after the flood everything was thoroughly repaired,” Mr. Fojtik said.

The Metro Station without the Metro

Around the corner from Malostranská Station, opposite the seat of the Office of the Government on Nábřeží Edvarda Beneše, you’ll notice a heavy door built into the wall under the hill on which sits the Villa Kramář. That door leads to one of the biggest enigmas in the history of the Metro.

Known as the “secret station on Klárov Street”, there is considerable debate whether the area inside was ever intended to be part of the metro or whether it was only meant to serve as a shelter for the communist government.

“It isn’t easy [to answer] because despite every effort, my colleague and I haven’t been able to chase down the information,” Mr. Fojtik said as to why the room was built. The documents about it remain classified. But maybe it’s not such a huge secret, since Google Street View allows a glimpse into the entry area.

Mr. Fojtik gave three possible reasons for the station. It was simply intended as a bunker, which is not especially controversial as it’s expected that a government would take such measures to protect itself. Secondly, it was built as a station which could also be used as a bunker, so very much in line with the existing station. Lastly, it was built as some sort of diversion.

The puzzling location was built over the period 1952 to 1960. It is a circular tunneled space, resembling Kobylisy Station in shape. There are two slanted shafts which could be for escalators but currently have steps. However, Mr. Fojtik doubts the bunker would serve as a station.

“The location of the entrance into the “secret station” is, in my opinion, nonsensical from a transport point of view,” he said.

However, the existence of the station – assuming it was intended to be one – forces a reconsideration of the Metro’s history. The Metro wasn’t opened until 1974. Its construction, though considered as far back as the end of the nineteenth century, was initially rejected in favor of the tram system. Perhaps, there was consideration 14 years earlier.

Legends that Aren’t

There are some stories about the Prague metro which aren’t true, according to Mr. Fojtik. One story is that the Metro includes a secret line which can take the government out of the city.

“A rumor has been circulating about the station on Klárov Street that there is a tunnel, which has a direct link to the metro system and if necessary the government can hop on there and leave by metro for the other side of Prague, where they will be taken somewhere else. Obviously, this isn’t true,” he said.

Mr. Fojtík further disputes the legend concerning another Metro legend. In 1972 during a test run, a train hit another train because the driver failed to brake in time. However, the accident has been seen as an act of sabotage in order for the Soviet built trains to be adopted.

“This isn’t true at all. The government had decided to import the Soviet trains before the first test of the Czech

transport system,” he said.

In the next article, we’ll look at some more of the wagons used as the inspiration behind the designs of the station. We will also take a closer look at the artwork which is there, but hidden from view.

Photo: Metroweb

Related articles

- Getting to the Prague Airport Is Going to Be Tricky for Awhile

- Prague among Top 3 European Cities For Public Transport Use

- Free Wi-Fi at Prague Metro Stations to Begin this Month

- Prague Transport Fines to Be Slashed In Half—But There’s a Catch

- The Hidden Meaning Behind the Prague Metro’s Stunning Color Scheme

Reading time: 6 minutes

Reading time: 6 minutes