Amidst all the charm and beauty that surrounds us in the center of Prague, it is hard to imagine anyone having a violent thought, or worse yet an impulse to oppress the whole nation of people who made such beauty possible. Yet the heart of man is an oft-contradictory machine, and nowhere is that more tangible than in the history of Bartolomějská ulice, named in honor of St. Bartholomew, whose church has graced the street since early 1700s. From the 1950s until the “Velvet Revolution” in 1989, the street housed the headquarters of the secret Czech police StB, a decidedly un-Christian organization that spied on, tortured, and killed thousands of Czechs.

It’s fascinating to consider the story of Saint Bartholomew himself as it relates to the story of the street. St. Bartholomew was one of Christ’s original twelve apostles who spread Jesus’ message in places like Ethiopia and India. After he converted the King of Armenia to Christianity, he was either beheaded or skinned and crucified upside down while still alive. His own violent end was just the beginning of other violent events that sadly came to be associated with his name. The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572 is still a quintessential historical benchmark of terror, when French Catholics (spurred on by the ruthless Catherine De Medici) began a slaughter of Protestants that lasted for weeks and ended up killing thousands of people. Tragically, St.Bartholomew’s legacy crossed another dark path in the violent past and present of Bartolomějská street in Prague’s Old Town.

In early 1700s, Jesuits built the Church of St.Bartholomew that still stands on Bartolomějská Ulice (at No.9), along with a convent and gardens. By the middle of 19th century, the property found its way into the hands of the Congregation of Grey Sisters of St. Francis. Up to a 1,000 nuns lived in the convent in its heyday. Nuns performed great deeds like working in hospitals and doing other charitable work. One night in 1950, the nuns were taken away to a detention camp in the country and the whole complex was taken over by the State secret police called StB (“Státní Bezpečnost” which basically means “State Security”).

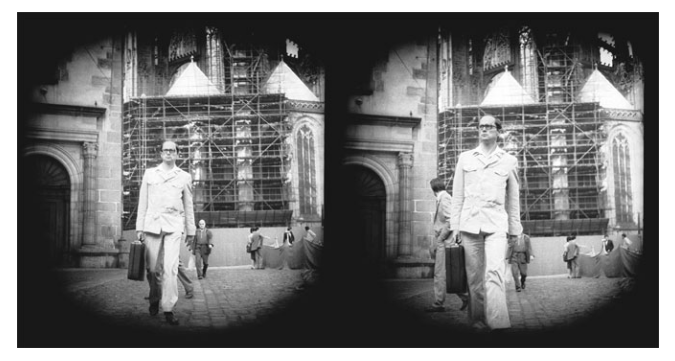

Actual STB footage

StB was formed in 1945 and dissolved in 1990 after the regime fell. It was closely controlled by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and was used as a very brutal and effective tool in maintaining power. The secret police looked for enemies of the state and found them everywhere, turning neighbor against neighbor and contributing to the creation of a paranoid, dehumanizing society at the peak of the Cold War. StB’s known tactics included torture, kidnapping, blackmail and spying by tapping telephones, following people, reading mail, and searching apartments. You can see some telling images from their photo archives in this illuminating exhibition.

The StB took over a whole block of buildings on Bartolomějská Ulice. The StB headquarters at No.4 became known as “The Tile” or “Kachlíkárna“, on account of the specific kind of tile that is used in its architecture. An incessant stream of people would be brought into the buildings for questioning and interrogation. The cells in the convent were turned into holding cells for the prisoners while St.Bartholomew’s church was used as a target practice area for the officers. The goal and effective outcome of StB’s activities was the creation of a climate in Czechoslovakia where anyone could be questioned for their loyalty to the communists. This led to neighbors informing on neighbors, as people had to survive somehow, even if it meant saving their skin at the expense of their friends. You could be arrested for something as innocent as complaining about a long line at a store. And if you were a real activist like the former President Václav Havel, your opportunity to be jailed on Bartolomějská increased exponentially.

This horrific climate of constant suspicion and betrayal made it very difficult to prosecute former StB members after the Soviet-backed Communists lost power. Many people’s names ended up in the archives of the StB either as collaborators or potential collaborators, whether they were in fact actively working with the communists or not. It has been proven that some files were faked for this exact reason – to squash the desire for retribution in those who might seek it. The StB archives that were released in 1996 included names of famous writers, religious leaders, and artists, among others. To this date, only a handful of former StB heads have been punished.

Actual STB footage, Prague

After the fall of the communists, the convent was given back to the nuns. Interestingly, to raise money for its restoration, they decided to turn its cells into a Pension called Unitas. It’s still operational today and is a popular tourist destination. Visitors can stay in refurbished rooms that once housed prisoners. One famous cell (No.6) is the one that supposedly contained Václav Havel during one of his imprisonments. The cell has an interesting story associated with it. Apparently, it came to be known as Havel’s cell in 1992 during the visit by Prince Charles. As they were touring the prison, Prince Charles asked Havel which cell he was kept in. It is reported that Havel was somewhat confused, perhaps overcome by the many difficult memories of his past flooding in. He pointed to a cell, which we now know as Havel’s but could have pointed to a number of other cells too since he stayed there a number of times. This is yet another instance of the effect StB had on the soul of the Czech Republic – the pain it has caused marred personal and public memory for generations.

The Bartolomějská Ulice of today still contains a major police station. Perhaps it would have been better to place this station somewhere else to avoid conjuring up the ghosts. On the other hand, it serves as a reminder of the line that can be crossed between serving the law and order of the land and becoming an oppressor of the people whose interests you claim to take to heart.

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes